Thank you to Mark for alerting us to this fascinating story. Here’s what the Guardian had to say this week:

What is the Heart of Voh?

The Guardian describes it as “the archipelago’s [New Caledonia’s] most famous mangrove formation: a light-green, heart-shaped patch of forest known as the Heart of Voh.”

It would not be unusual for the Guardian to get several things wrong in one sentence, and this story is not unusual for the Guardian. What it is – or what it has been until relatively recently – is actually a heart-shaped hole in a stand of mangroves, as the Guardian itself makes clear moments later:

“It was just a yellowish salt flat,” says Dr Cyril Marchand, a mangrove expert at the University of New Caledonia. “No mangroves could survive there.”

The Heart of Voh was made famous by the aerial photograph by Yann Arthus-Bertrand, who presumably stumbled upon it by accident. It features on the cover of one of his several books.

Once known about, it became a tourist attraction. You can have a trip on a light aircraft to, I dunno, lean out of the window and get a much worse snap than the ones several pros have taken already, or try to get the ultimate brag-selfie with it in the background (try not to drop your phone, or fall out of the plane).

(I was out on the Broads yesterday, and saw a bunch of daytrippers being shown a derelict whaler covered in a black tarp – a tourist attraction is anything that the tour guide can point to and say two sentences about. In this case, they were snapping away at the floating hulk as if it was something to put on a slideshow and be shown to a victim later.)

The Guardian says:

In the late 1990s the pale, barren surface of the heart contrasted sharply with the green mangrove forest around it, creating its iconic silhouette when viewed from above. Sitting slightly above the surrounding mudflats, the heart’s soil was dry and salty – too extreme for vegetation to grow.

I have never been to the Heart of Voh, but I would bet the 12-sided mock-gold and mock-silver coin on the table in front of me right now that the Heart is actually lower than the surrounding mangroves, not higher.

So they begin by calling it a “heart-shaped patch of forest” as if it’s Lothlórien, and the next, they admit it’s actually a dead zone, where nothing can grow.

Now, though, teh Climate Crisis is causing sea-levels to rise:

…waters along New Caledonia’s west coast have risen about 2mm a year for several decades. As tidal waters flow into the heart more frequently, the salty soil becomes diluted…

The less-salty soil means that mangroves can colonise the heart, and threaten to obliterate its outline, because there will just be one continuous block of green, instead of a block of green with a heart-shaped hole. Oh woe!

Some Ecology

It’s a pity that the Guardian did not opt to educate its reader about coastal ecology and the processes controlling the development of mangroves. In the UK, we don’t have any mangroves, which is probably why I find them exciting. Our analogue is salt marsh, but here the woody plants are few and are up the top of the shore, not at the bottom. I will not go into great detail on this, but one way to think of such habitats is as a series of plant species altering the environment to their own detriment and being replaced by others.

Coastal waters are often full of fine sediment, which settles out in low-energy areas. Bare mud is colonised by pioneer species, whose presence increases sedimentation by slowing the water that flows through them, which therefore drops more of its sediment. The raised surfaces thus created enable new species to colonise, which are able to out-compete the pioneers. These are themselves out-competed by yet more species as the marsh rises. Ultimately what was once tide-swept mud may even rise out of the range of tides altogether, and transition to fully terrestrial habitat.

The dead Heart of Voh was a place so salty that nothing could grow there. This is not an unusual circumstance in mangroves. If you open Google Earth and tool around the tropics until you find a mangrove coast, the chances are you’ll see areas just inland that are apparently devoid of life. These are hypersaline areas. [Such areas do rather upset the neat sequence I described in the previous paragraph. Things are not that simple.]

Consider salinity on a regularly sloping shore: where on the slope, from Mean High Water Springs to Mean Low Water Springs has the highest salinity? Well, it’s the top of the shore. Here, the tide reaches occasionally, but the sea water then evaporates, concentrating the salt. Further down, we have daily or twice daily floods, meaning that the water of the mud does not get any more concentrated than sea water.

The situation where there is a basin is potentially more extreme: imagine a single tide flooding the basin, and for the hot tropical sun to evaporate all that water. There are several means by which such depressions arise. As an example, a natural levee tends to get created on the edge of mangrove blocks (as well as other wetland habitats) because the sediment quickly drops out of the water when it hits vegetation. The resulting hypersaline conditions in the basin kill everything, and you end up with a salt flat.

What puts an end to hypersaline conditions? There are several ways this can come about. The important thing to remember is that coastal habitats are in a constant state of flux. Options include increased rainfall, higher tides (as blamed here by the Guardian) or the initiation of a new drainage channel. These formations are all made of soft mud, and a storm can re-set everything. For the Dead Heart of Voh, I suspect that the drainage of the basin is now sufficient to flush more of the salt away. That’s all you need to enable mangroves to (re)colonise. Higher tides may be to blame, and indeed tides and drainage go together. But the Guardian’s surprisingly low-ball 2 mm a year is only 6 cm in thirty years, and this is a rate of rise that sedimentation can easily keep up with.

The Pristine Environment of New Caledonia

The Guardian blathers on about the Heart of Voh as if it is a permanent and large feature – it’s temporary and 200 m across, and you can only appreciate it if you fly over it. In the grand scheme of things, it’s trivial. It is surrounded by very similar hypersaline features, albeit ones that don’t resemble a heart. This view is from 2002, despite the copyright label. It shows the heart and a few of its less-celebrated but otherwise similar brethren:

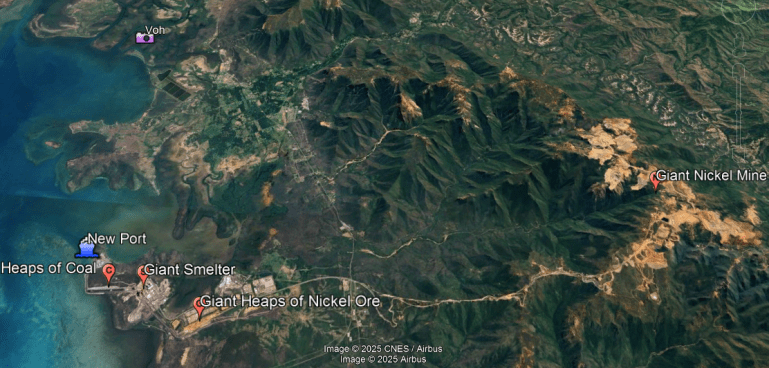

It might have been useful if the Guardian had widened the scope of its article a little, geographically speaking. Because if it had done so, the word “pristine” might have been struck from the copy. The following, more broad view is about 10 miles wide. I’ve labelled one or two things. The pristine mountain in the east has been destroyed by the Koniambo nickel mine.

The nickel ore is put on a conveyor (not labelled) and taken down to be piled up ready for smelting (piles of ore and smelters labelled). The development necessitated a new port, so that the ingots, or whatever they are, of nickel can be taken away. Of course, you need a lot of coal to run the smelter (piles of which are labelled).

The squares immediately south of the heart are not tennis courts, but probably evaporation basins. If you paste this into Google Earth, you can inspect the whole scene for yourself: -20.983396° 164.729182°

Now, I’m not against development. The people of New Caledonia are within their rights to exploit their nickel resource. But I’m quite sure this is not what “pristine” looks like.

The Strange and Convenient Inversion of Good and Evil

As observers of Earth, it’s as well to see the barren salt flat and the dense mangrove as having an equal value. Succession often goes in cycles; gaps appear, and those gaps are eventually filled. You cannot have a rainforest without a tree dying, falling over, and creating a gap for new trees to compete for light in. But generally, the likes of the Guardian recoil in horror at dead zones (some dead zones are not part of a cycle like this, and there are permanent dead zones behind mangroves on arid coasts). I’m quite sure that our alarmist friends would have got even more excited about the Heart of Voh if it was a green oasis surrounded by a wasteland of dried, cracked hypersaline clay, and if the clay was smothering it (because of teh Climate Crisis). As it is, there is a strange inversion here: the feature they want to see preserved is a dead zone now. Life is spreading into it, and that is somehow horrifying.

Generally, the terror that they have is of rising sea levels destroying mangroves. Now the terror is that rising sea levels will encourage the blighters. Won’t they just stay in the neat boxes we want them to?

Brilliant. Thank you .

If only Guardian journalists could see beyond “the climate crisis” they might be able to write something half as interesting and informative as your work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

From that Guardian article, this stood out for me –

“‘We can’t let it slip away’ –

Protecting the heart is a priority for the local community and tourism operators. For over 15 years Günter Gerant, a pilot at tourism flight company Haut Vol, has shown tourists the Heart of Voh by air. He says it is one of the most famous things to see in New Caledonia. “We [Haut Vol] started the discovery flights because everyone wanted to see the Heart,” Gerant says. The veteran pilot plays an important role in the local economy. “People come to see the Heart, our mangroves and our coral reefs so it’s really important to maintain these ecosystems for our livelihoods,” he says.

You have to wonder what he means by “a priority for the local community and tourism operators”.

Wonder if the heart will get pruned?

LikeLike

dfhunter,

Two things struck me about that Guardian article.

Jit has brilliantly skewered the first – blaming climate change for bringing life back to a dead zone, by enabling mangroves to grow there, the mangroves that Guardian articles regularly say are threatened by climate change.

The second is arguing that the loss of the heart, visible only from the air, will damage the tourist trade – that’s the tourist trade dependent on long-distance flights to get there and short flights to photo the heart, that the Guardian regularly bemoans as causing climate change.

Truly the Guardian hit a new low – quite a feat! – in that article,

LikeLiked by 1 person