Sceptics are often criticised for being all too willing to dispute climate research findings and yet not so willing to do any scientific research of their own. The received wisdom is that you are supposed to enter into a scientific debate by doing your own science; alternatively, you can just shut up and accept the findings of those who have at least put in the effort. It’s an argument that has merit but pays little regard for the enormous effort required to go from a place of layman scepticism to one of fully informed scientific participation. So, is it fair to deny anyone an opinion on a group’s output just because they have failed to gain the qualifications required for group membership?

Effort barriers place the majority of us in the position of having to take on trust what the explorers of truth claim to have discovered. I, for one, am not about to embark upon a climatology degree followed by years of research, and so should feel obliged to accept the advice of those who have. On paper, this looks like a predicament that simply has to be accepted by those of us who have been daunted by the effort of first-hand exploration. But since there are supposed to be processes in place to ensure the exploration’s probity and integrity, surely the layman’s predicament resulting from this effort barrier carries little actual peril. What are the chances that, when every suitable authority on the planet confirms the existence of an objective reality, the truth should turn out to be entirely different? Yes, the majority of us have a huge effort barrier preventing us from gaining first-hand confirmation, but surely that isn’t a problem in practice. And, surely, there are plenty of historical examples that demonstrate that the implications of the effort barrier need not be of concern. Surely, history has shown that when every suitable authority on the planet is there to reassure you of the nature of reality, you can relax and take it on trust. Can’t you?

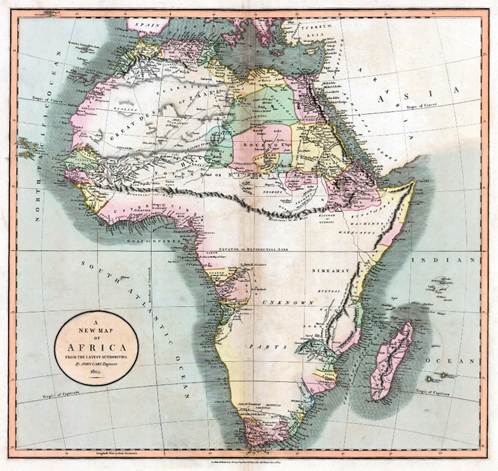

Well, let’s see. Let us go back to the turn of the nineteenth century, before Google Earth was a thing, and when the vast majority of us had to rely upon fusty old maps drawn up by explorers to know what was out there (apart from the dragons, of course). Viewing these maps, it would have been impossible to miss a huge glob of land sprawled across both hemispheres. It’s called Africa and it wouldn’t have taken a genius to work out that the effort required to confirm its existence first-hand would be considerable (there being no charter flights in the pre-Google Earth era). But not to worry; those pre-Google Earthers with no appetite for tropical exploration still had their maps to fall back upon. Here’s just one example that illustrates what the maps were all saying at the time:

Yep, that looks like Africa. Admittedly, it’s a bit short of detail regarding the southern interior, but that’s only to be expected given that Africa is dissected by a huge, impenetrable mountain range extending fully from the eastern to western coast.

Say what again? Huge, impenetrable mountain range? Extending from coast to coast? How did that get there?

Well, it got there because those who could be bothered to make the effort went out and ‘found’ it. And, for the benefit of the lazy laypeople who stayed at home, they drew up detailed maps for everyone’s delight and education. These mountains even had a name: the Mountains of Kong.

To be precise, the map shows two mountain ranges that conveniently merged to provide the aforesaid barrier: there were the Mountains of Kong and the Mountains of the Moon. Both ranges were huge, both were impenetrable, both were well-documented and both shared the peculiar geographical feature of never having existed.

The non-existent Mountains of Kong were first ‘discovered’ by the famous Scottish explorer Mungo Park and committed to print by the English cartographer James Rennell. The Mountains of the Moon date back even further, having first been mentioned in Ptolemy’s Geographica of AD 150. It fell to cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith to firmly establish the conjunction of these two fabled ranges, quickly followed by London cartographer John Cary, producer of the map featured above.

There ensued an enthusiastic rush to reproduce maps confirming the extent and grandeur of the mountains; so much so that historians Thomas Basset and Phillip Porter were subsequently able to identify an ensemble of forty such maps, published between 1798 and 1892. It seems that every cartographer of note had got in on the act. Even more puzzling, there would be no shortage of intrepid explorers who were willing to testify to having seen the ranges first hand. Most notable of these was none other than Captain Richard Francis Burton (he of Kama Sutra fame and co-discoverer of the source of the Nile), who as late as 1882 testified to the Royal Geographical Society of having seen for himself the ‘towering masses of granite…upstanding outcrops resembling cathedrals and castellations in ruins; boulders of enormous dimensions; pyramids a thousand feet high, and solitary cones which rise like giant nine-pins’.

The reality is that the Mountains of both Kong and the Moon had started out life as simple conjectures; mountain ranges whose existence would explain the seemingly eccentric route taken by the River Niger. True, there were a few prominent mounds of earth to be found in the real African district of Kong, but nothing that could explain the Niger’s eccentricity or the subsequent corroborations of towering mountains dissecting a continent. I guess it all started out as well-meant theorising, but then one thing led to another and, before you knew it, a Massif Central of bullshit had established itself as an incontrovertible truth, served up for the benefit of all those who had themselves been deterred by the effort barrier that is African exploration. Few fancied the malaria, but many could still afford an atlas.

Eventually, of course, the bemused expressions of the growing number of returning explorers, unable to hide their disappointment, eventually led to the debunking of a continent-splitting mountain range. Even so, in 1928, the Bartholomew’s Oxford Advanced Atlas was still proudly declaring the mountain range’s existence, placing it carefully at 8° 40′ N, 5° 0′ W.

History does not record whether prior to the debunking there had existed a stubborn group of anti-cartographic mountain deniers who unreasonably impugned the integrity of both explorer and cartographer alike. There being no special campaigning undertaken by Mountains of Kong alarmists, I doubt that a party-pooping group of sceptics would have had a role to fulfil. Everyone would have just taken the maps at face value and moved on with their lives. I certainly don’t think anyone would have been saying to the average bloke in the street, ‘Either go out there to see for yourself, or shut the f*ck up’.

Nowadays, international travel is open to many, and Google Earth is available to the remainder. So, there is no modern-day equivalent of the hapless map-reader, spoon-fed with fanciful but authoritative looking models of the world. Or is there? I know I’m not meant to say this, but I can’t help feeling a little bit uneasy regarding the huge trust the world has had to place in the output of a comparatively vanishingly small coterie of climate modellers who claim to have seen the future for themselves. Not having been there myself, I am certainly in no place to judge. And yet I still like to think there is a role for uninformed scepticism. I’d like to think that, back in the day, I would have appreciated just how difficult it must be to map a continent so large and uncompromising as Africa. I’d like to think that I would recognise that 40 maps all saying the same thing isn’t necessarily as convincing as it is meant to be. I’d also like to think that being open-minded about the existence of a huge chain of massive nine-pins that conveniently split a continent in two would be a perfectly reasonable position to take. And I would like to think that none of this would require me to have gained qualifications and experience in cartography, nor a passport stamped with every African country. Sometimes it isn’t about having been there and bought the tee-shirt; sometimes it’s just about recognising the purpose and value of tee-shirt slogans.

There are numerous examples from history of the scientific/political/elite consensus being subsequently overturned. Whether current climate science will in due course be overturned, I have no idea. I am not a scientist, and I don’t question the science regarding the effect of greenhouse gases on global temperature. But I do know that there isn’t agreement as to how much warming will be caused by any particular level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and I don’t think it’s unreasonable as a lay person to doubt the more extreme climate alarmism that is out there. Some of the more hysterical claims try to wrap themselves in “the science”. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see those claims disproved in due course. I also doubt that the urban heat island is sufficiently taken into account. There are many layers to these questions, and many nuances, yet a lot of alarmists see this in terms of black and white, of good against evil. That doesn’t sound much like science to me.

LikeLiked by 3 people

A key weakness of climate science is that it deals with the future, not the present. So to continue the analogy with fictitious mountains, the cartographers would be specifying that, although Africa is presently flattish, orogeny was imminent on a transcontinental scale, unless the peoples of the world made amends for their sins.

Is there another branch of science that would put up with climate science-style “projections”?

Meanwhile, I like the dogheads. Where do the dogheads live? Further east. Over the horizon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks John for another though provoking post. My 1st reaction was to think about Stephen McIntyre at Climate Audit & the “hockey stick”. Maybe wrong, but to me he started the push back against ” you can just shut up and accept the findings of those who have at least put in the effort”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

PS – Jit has lost me with “dogheads”, heard off dogends though 🙂

LikeLike

Dogheads? Follow the link in Jit’s comment to learn more.

LikeLike

Did follow the link, and Dogheads led to a history/folklore rabbit hole. First link –

Cynocephaly – Wikipedia – partial qoute –

“Cynocephali appear in the Old Welsh poem Pa gur? as cinbin (dogheads). Here they are enemies of King Arthur‘s retinue; Arthur’s men fight them in the mountains of Eidyn (Edinburgh), and hundreds of them fall at the hand of Arthur’s warrior Bedwyr (later known as Bedivere)”

Well that got me interested as I’m from the Edinburgh area originally & read the Y Gododdin years ago. Interesting link – Kingdoms of British Celts – Votadini / Guotodin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Searching an old Encyclopaedia Britannia for “Paris Green,” I happened across the entry for Mungo Park on the next page. Here is the description of his last trip:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Since writing this article, I have found the following link:

https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/fabled-and-false-the-mountains-of-kong/

I found it interesting because it alludes to the Mountains of Kong appearing in an atlas as late as 1995 (i.e. in Goode’s World Atlas). It also includes the following quote from the two historians mentioned in my article:

LikeLike

As a further example of misplaced trust in the ethic of cartographic accuracy and the application of scientific methods, one could cite the phenomenon of the island of California:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Island_of_California

Ironically, one of the factors that helped the misconception to flourish was a megaflood that occurred in 1605:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_flood_of_1605

I say ‘ironically’ because a modern-day trust in the ethic of accuracy and the application of scientific methods lies behind the common misconception that we live in an unprecedented era of mega-flooding. Well, I suppose that might be a reasonable belief if one were to ignore the Californian megafloods of A.D. 212, 440, 603, 1029, c. 1300, 1418, 1605, 1750, 1810, and 1861–1862.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As opposed to things appearing on maps that weren’t actually there, our media will probably never tell us about NASA’s satellite mapping of the boreal forest:

https://joannenova.com.au/2026/02/climate-pollution-causes-boreal-forests-to-grow-12-recklessly-spreading-greenery-in-arctic/

In 40 years the area covered has increased by 844,000 sq km. Coincidentally that is very close to the area of Amazon rainforest lost over the same timescale.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Mike: there’s an irony here, which I might put up a brief post about, if I’ve time.

LikeLike