The topic of Lake Chad cropped up on Cliscep the other day, in the context of a comment sent to Robin on his “West vs the rest” hypothesis. This is the relevant excerpt:

Many developing nations — particularly in Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and small island states — are already experiencing severe climate impacts and are among the most vocal advocates for urgent action. Lake Chad is a stark example: once covering around 10,000 square miles and supporting 40–50 million people, [it] has shrunk by around 90%, contributing to humanitarian crises and regional instability. Countries like Chad are highly engaged at COPs precisely because the stakes for them are existential.

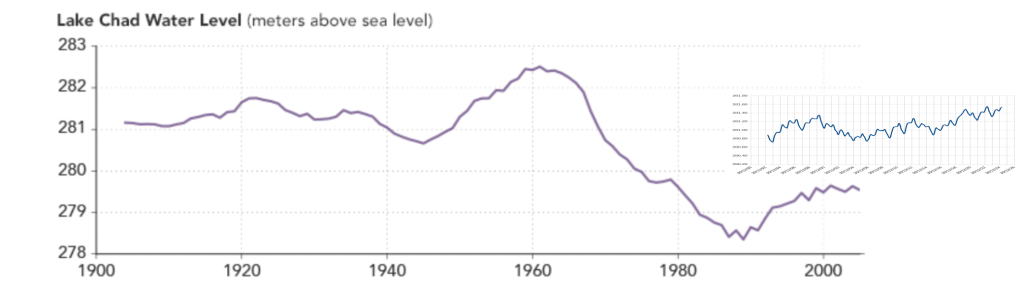

The allegation is one we have heard before. (Never mind that the figure of 40-50 million people supported by it is pure bunkum.) A few years ago, when Mark penned Niger Negatives, I looked up some data on Lake Chad levels. There was an old reconstruction showing the main fall in water levels took place in the 1960s, and satellite altimetry data from DAHITI showed no cause for alarm. Of course, that data necessarily ended in 2022, when the comment was made, so perhaps Robin’s correspondent had something more up-to-date. Here is how the most recent DAHITI data, available here, look:

The years are somewhat obscured, but the timeline runs from 1992 to 2025. Of interest may be that the lowest value in the series was in 1993, and the highest in the series was in 2024. I see no cause for alarm here. If the climate “crisis” has evaporated Lake Chad, it must have done it before anyone was even aware of the problem.

The historical reconstruction looks like this. It comes from Earth Observatory here. I have spliced on the (running average to remove annual fluctuations) values for the DAHITI data. As you can see, although they both claim to be measured in metres above sea level, their baselines are offset. Nevertheless, there is still no evidence of a climate “crisis” in the data.

Mentioned on the Earth Observatory page from which the reconstruction comes was a French expedition to the region in the first decade of the twentieth century. Some excerpts follow from Tilho’s presentation to the Royal Geographical Society in 1910, pertaining to the level of Lake Chad his expedition found:

When we arrived at Lake Chad an interesting and difficult geographical problem presented itself before us—

(1) is Lake Chad gradually disappearing, or are its fluctuations subject to a fixed law?

p.271

You understand our curiosity four years after having made our first map of Lake Chad, to see what was the aspect which this constantly changing lake was likely to present. When we arrived in the vicinity of the lake, we learned from the natives that caravans were crossing on dry land the northern portion, which in 1904 we had navigated on board the Benoit Garnier; that the central portion was merely a marsh where no boat could pass; whereas in the southern portion certain channels, which had formerly been closed to navigation, had become once more practicable. The drying-up of the northern portion, we were told, had been so rapid, that a great quantity fish had not had time to flee southwards, and had taken refuge in the depressions, where they had been asphyxiated in the few inches of stagnant and muddy water that had been left behind. For the natives it was quite like a new Miracle of the Fishes; they gathered them in baskets. Even to-day large areas are covered with dead fish. The herds of cattle suffered greatly from this sudden transformation the lake. The stagnant water, saturated with salt, and charged with decomposed matter, became poisonous, and animals perished by hundreds. The rhinoceros, the hippopotamus, the elephant, themselves, disappeared southward in the wake of the retreating water.

p.272

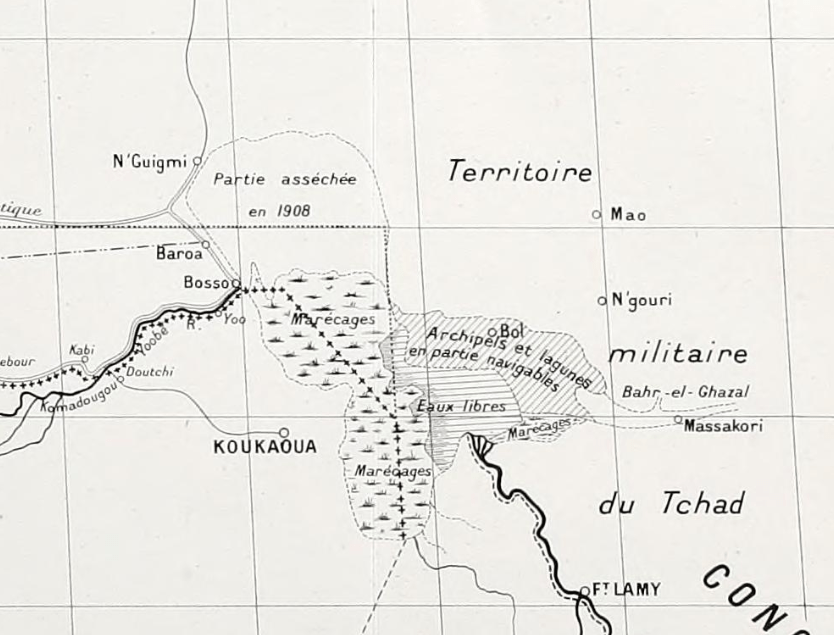

Tilho and crew divided Lake Chad in 1908 into four zones:

1. The dried-up zone

2. The marshy zone

3. The navigable zone

4. The lagoon zone

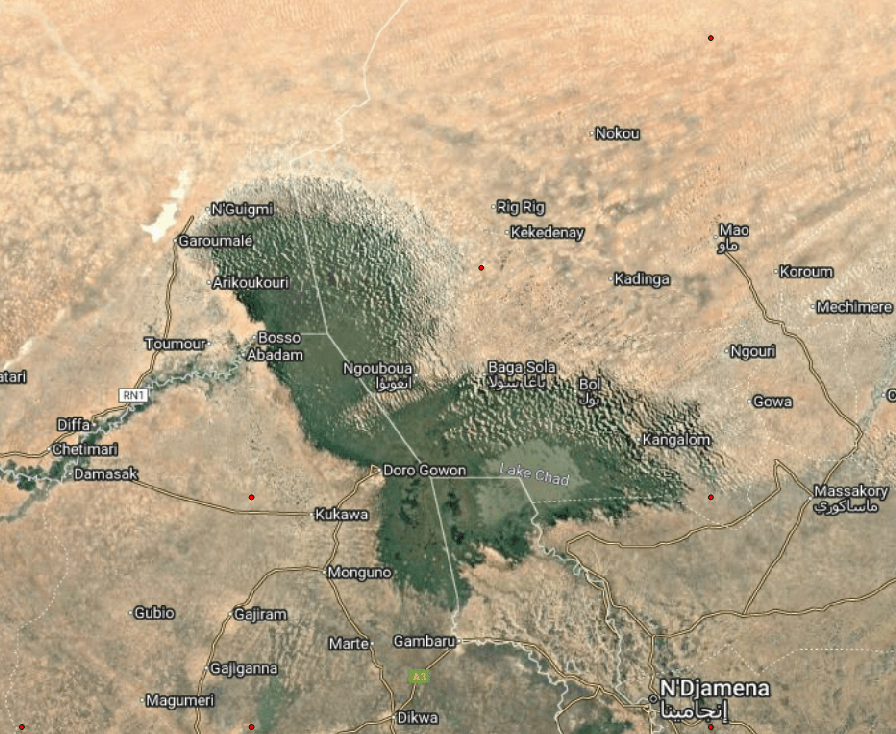

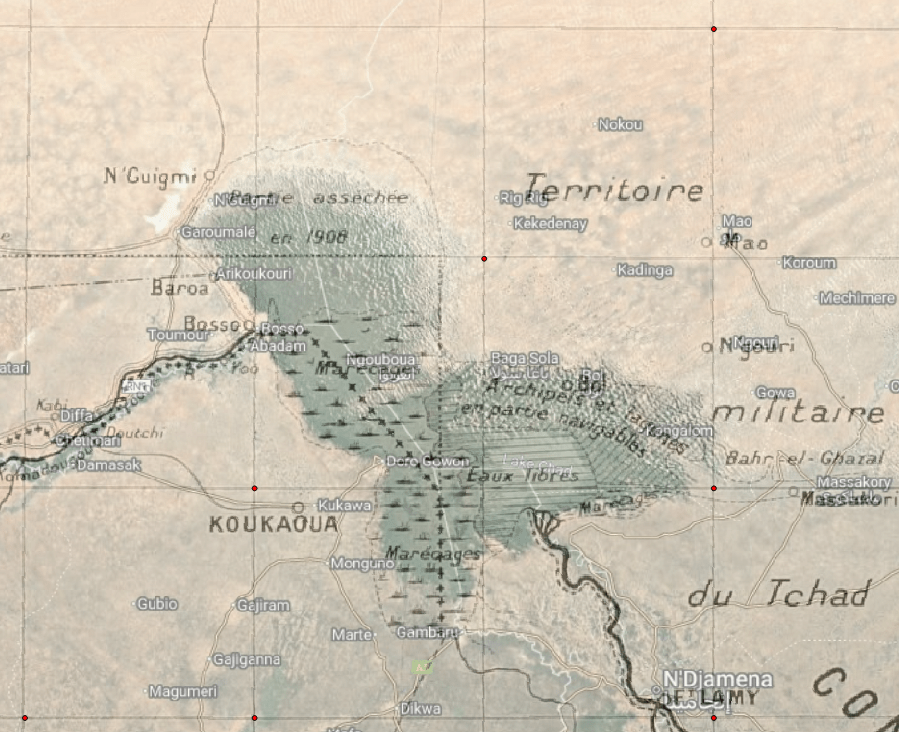

These are shown on their contemporary map below. For reference, it is followed by a recent Google Earth image, and then an attempt to superimpose the old over the new. It’s not quite in the correct place, because my georeferencing went awry even though latitude and longitude was labelled on the French map. [A congratulatory thimble of Scotch if you can guess why. Answer to follow in a comment.]

Slight offset or not, the map and photograph are substantially similar. In particular, the navigable zone coincides with today’s open water in the southern part.

Now we go forwards in time to an image on the Earth Observatory page, showing a very early satellite photograph of the lake (1963). Here we can clearly see the northern limb is open water.

There is a seeming disconnect between the long-term reconstruction shown on Earth Observatory and the description of Tilho. The reconstruction shows high water, Tilho says the northern limb was dry. The reconstruction certainly matches what we know from 1963 onwards, but it’s dubious whether it captured the long-term variation before then.

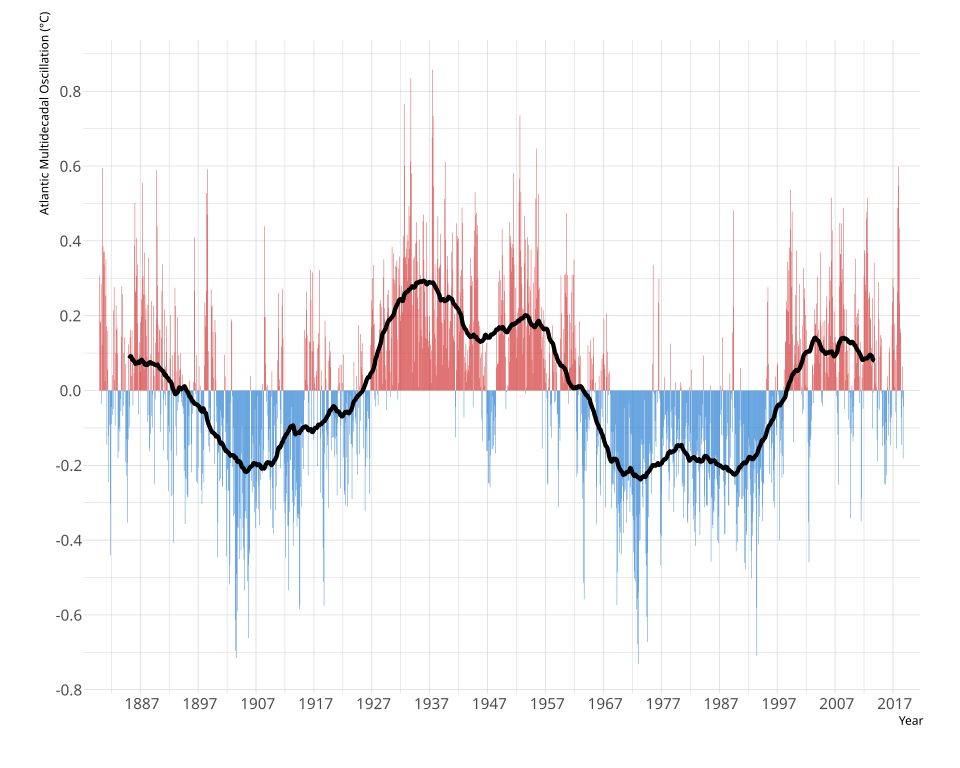

The Earth Observatory page also draws the reader’s attention to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. This has a period of about 70 years, and although it does not match the reconstruction particularly well, there are certainly hints that the changes in Lake Chad might be periodic in nature rather than linear, especially when considering Tilho and colleagues’ observations from 1908. (These match the AMO better than they match the reconstruction.) The image comes from Wiki at this page.

If I may make a Feynmannian attempt to disprove myself here: a critic might say I am using the fact that the bath is full to prove the bathroom has been flooded. There is a shallow sill between the northern and southern limbs of Lake Chad, such that the northern limb will not flood unless the southern reaches a certain depth. So all the oscillations under the sun don’t matter, as the northern part stays dry unless a certain water level is breached. In my defence, I might say if that is true, then the sill was last flooded a long time ago, before any hint that there was such a thing as a climate “crisis.” (Referring to the reconstruction, it was some time during the steep descent of the late 60s.)

A final point to make is that, if Lake Chad is sitting at the level of the aquifer, it will stay wet until the two become detached. Thus, if the locals decide to engage in irrigation to support farming, the result could be a once-and-done disappearance of the remainder of the lake.

/message ends

Jit, was the French map using longitude based on Paris rather than Greenwich? I am just off to check when the scientific community formally agreed to settle on Greenwich; maps on the ground in Chad may, however, have taken a few years to catch up with that scientific decision. Regards, John C.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Hello John – yes, you got it in one. The prime meridian was Paris, so when I carefully georeferenced the map, it wound up about 2.3 degrees west of where it should have been. The latitude was, however, correct.

I believe the change may have come in in 1910, so this would have been around the last time it was used. (I can’t remember so do correct me if your research turns up a different year.)

LikeLike

Two clear messages emerge from that very clear analysis:

First, history is important. People who look only at the last few years or decades are always going to miss the bigger picture and thereby lead themselves (and potentially others) astray.

Second, the lazy trope that a drying Lake Chad “proves” a climate “crisis” is not an isolated one. This sort of thing goes on all the time – hence my occasional series of articles, including Niger Negatives (thanks for the plug, by the way :-)).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Memories of a cold walk in southern Paris’s 14th arrondissement some years ago suggested that the Paris observatory had its being thereabouts. And a search on my computer for the Paris Observatory informed me that both “the Greenwich Meridian became the global standard in 1884” and that “The Greenwich Meridian replaced it [i.e. the French longitude reference line] as the international standard in 1884, with France officially adopting it in 1911.”

Presumably the Anglo-French Entente Cordiale of 1904, although related to colonial matters, did not extend to settling the turf war about the geographical datum of longitude. Quel dommage.

Two other interesting snippets from the computer:-

“The line, originating from the Paris Observatory, was used to define the meter as one ten-millionth of the meridian’s length.”

“Cultural Impact: Popularized by Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, the line is known as the “Rose Line” and connects ancient sites like Chartres Cathedral.”

Regards, John C.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As ever, the anthropogenic “severe climate impacts” on bodies of water such as Lake Chad neglect other, more consequential anthropogenic activities. The most significant is upstream irrigation development. As the biggest river of the Lake Chad basin, the Chari/Logone River contributes approximately 90% of Lake Chad’s water input. This study, for what it’s worth, concluded that, since the 1960s, the relative contribution of human activities accounts for more than 80% of the total water loss in Lake Chad.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022169418309582

And irrigation investments continue, for example

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/12/02/world-bank-provides-200-million-to-strengthen-irrigation-services-in-the-logone-river-valley

LikeLiked by 3 people

Jit – thanks as usual for your quest/labours for historical context to these “Lake Chad is a stark example” assertions we hear all the time. I have no doubt the ‘sustainability expert’ that robin quotes truly believes “severe climate impacts” are causing this, it must be so in her mindset.

ps – as a fun aside, went to Paris for new year with friends years ago. I took a bottle of Champaign to the Arc de Triomphe to celebrate new year & dropped/smashed it just as new year struck 😦

Never been Seine since 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

potentilla,

It’s interesting that the World Bank irrigation project is the sort of thing that ticks lots of UN COP-type boxes (or is certainly framed as if it does):

…The project will benefit different groups of poor people: poor farmers, particularly women, by improving their ability to increase irrigation productivity and a likely doubling of cropping intensity; and through infrastructure investments and support for intensifying production, improved irrigation and drainage. In addition, improved flood management, including the early warning system in 300 km, would benefit the residents of the Logone Valley, both in Cameroon and Chad.…

How ironic if the sort of thing done at the behest of climate-obsessed COPs helps to create a situation that then enables the sort of people who attend climate-obsessed COPs to scream “See – this is the result of the climate crisis”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mark, I’m sure people are driven to cynicism by the constant attempts to blame the concentration of a diffuse gas for every problem under the sun, even when there are obvious candidates for blame that are locally a thousand times more powerful.

What surprises me is that the true believers don’t have a lightbulb moment that at least nudges them towards “mild scepticism.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lake Chad is a perfect example of how problems always seem to be framed nowadays. Nothing other than climate change is allowed to be a primary concern. If there are others, then their pertinence is always evaluated in terms of how they exacerbate or mitigate climate change. There may be war in the area, but that is only a concern in so far as it may exacerbate the impact of climate change. Over-irrigation may be a problem, but again that is only a concern in so far as it may exacerbate the impact of climate change. Similarly with governmental incompetence in all its manifestations.

There is another thread active at the moment here on CliScep that illustrates the same issue in a very different context. Ecoanxiety is on the increase and, according to a study, the use of apocalyptic language in the media is connected to this rise. But is that a problem? Well not if it leads to a greater sense of urgency to mitigate the impacts of climate change. In fact, ecoanxiety could be a small price to pay according to the authors. However, if it leads to apathy and reduced motivation to act, then it becomes a problem. We are no longer capable, it seems, of treating problems for what they are – potentially serious problems in their own right that may or may not have a secondary relevance that relates to climate change. We are in a poor position when we can no longer apply the basics of decision theory strategizing.

LikeLiked by 3 people

As a postscript to my cold walk in Paris’s 14th or Observatory arrondissement (mentioned above), my memory has been jogged overnight. I now have a memory of a “gunsight” in a park in southern Paris; the “gunsight” being in my memory the line of the north-south meridian through Paris.

Research shows that my memory is not entirely false. There is a column, la Mire du Sud, in Montsouris park (https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g187147-d14177882-Reviews-Mire_du_Sud-Paris_Ile_de_France.html) which is almost due south of the Paris Observatoty which itself is just south of the Luxembourg Gardens and the Senate building. The Mire du Sud column is indeed topped by what resembles a very large rifle sight.

One of the meanings of “mire” in French is “sight” as in gunsight. And Wikipedia shows (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parc_Montsouris#Meridian_of_Paris) that originally the column did indeed mark the meridian through the Paris Observatory but that, subsequently, the column was moved and now stands some 70 metres east of the meridian.

As I point of qualification regarding the original definition of the length of one metre (mentioned in the earlier post) as being one ten millioneth of the length of the meridian, I should say that the definition refers to the distasnce from the pole to the equator (and NOT from pole to pole).

Regards, John C.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John R, you wrote, “We are no longer capable, it seems, of treating problems for what they are – potentially serious problems in their own right that may or may not have a secondary relevance that relates to climate change. We are in a poor position when we can no longer apply the basics of decision theory strategizing.”

With the statement above I think you have captured the essence of the West’s hypnotic political state these last few years, essentially since the COP in Copenhagen at the end of 2009 when the rest of the world rejected the Western governments’ absolutist war-on-CO2 stance.

Copenhagen should have been the last stand of Western governments’ climate mitigation policies in favour of domestic adaptation (or ‘protect and defend’). Instead our Western governments continued as though nothing had changed (i.e. as though they still ruled the world) irrespective of the damage that has done – and continues to do – to Western economies. As you inply, almost everything strategic is first seen through the lens of climate change irrespective of its relevance to any given threat.

It is a bizarre situation that we (mostly) Europeans find ourselves in – the Americans seem to be coming to their senses energy/climate wise, even though president Trump and his other policies are not to everybody’s liking. Fortunately there seem to be signs that in the UK the ‘uniparty’ stance is cracking as reality intrudes more and more. As Ayn Rand said, “We can evade reality, but we cannot evade the consequences of evading reality …” for much longer. https://www.azquotes.com/quote/425641

Regards, John C.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John C, I very much agree with your observation re COP15 in 2009 that ‘Copenhagen should have been the last stand of Western governments’ climate mitigation policies …’ So it should. You may recall that, in my West vs. the Rest essay, I cited this comment on the outcome of COP15 from Rupert Darwall’s book ‘The Age of Global Warming‘:

That could have been a clear opportunity for the West to face the truth and adopt energy policies that took account of reality. But no, we continued with the arrogant and foolish view that the white man should set an example. Unsurprisingly non-Western people were not interested.

LikeLiked by 3 people

John R:

Nothing other than climate change is allowed to be a primary concern. If there are others, then their pertinence is always evaluated in terms of how they exacerbate or mitigate climate change. There may be war in the area, but that is only a concern in so far as it may exacerbate the impact of climate change. Over-irrigation may be a problem, but again that is only a concern in so far as it may exacerbate the impact of climate change. Similarly with governmental incompetence in all its manifestations.

Indeed, that is the issue. In their continuing tradition, the Guardian has another such article in exactly the same vein just now:

“Barracuda, grouper, tuna – and seaweed: Madagascar’s fishers forced to find new ways to survive

Seaweed has become a key cash crop as climate change and industrial trawling test the resilient culture of the semi-nomadic Vezo people”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/dec/24/madagascar-coastline-vezo-people-fishing-climate-change-adaptation

Climate change and industrial trawling. I wonder which is the predominant issue? But in the world of Guardian journalists, it’s always climate change that comes first:

Along Madagascar’s south-west coast, the Vezo people, who have fished the Mozambique Channel for countless generations, are defined by a way of life sustained by the sea. Yet climate change and in….

….fish populations began collapsing in the 1990s and have declined sharply over the past decade.

Rising sea temperatures, coral bleaching and reef degradation have destroyed breeding grounds, while erratic weather linked to warming oceans has shortened fishing seasons…..

Industrial trawling is relegated to a subordinate role. But this is the reality:

https://blueventures.org/a-victory-for-small-scale-fishers-and-marine-ecosystems-destructive-bottom-trawling-banned-in-madagascar/

...Bottom trawlers, vessels that drag weighted nets over the seabed to scrape up fish, land around 19 million tons of seafood annually, almost a quarter of marine landings and more than any other fishing method. The practice is hugely devastating for vulnerable seabed habitats as well as those who rely upon them to eat and to live. Delicate habitats like coral reefs and seagrass meadows that provide food and shelter for a huge diversity of sea creatures can be ripped to shreds and may never recover.

In Madagascar, bottom trawlers mainly target shrimp for export to the EU and China. With growing demand in recent years, fishing from both industrial and small-scale sectors has intensified pressures on the stock, leading to overfishing…..

LikeLiked by 1 person