Populations of sea mammals often follow a rather predictable pattern through history. Here’s how she blows:

1) They are doing quite well, thanks

2) They get discovered by humans

3) They are slaughtered in large numbers, and only populations in remote areas survive

4) Brought to the brink of extinction, humans make a pact to let them alone, or partially alone, or alone in some places

5) The population recovers to a greater or lesser degree

6) The population becomes “threatened” by climate change, and the species is used as a talisman to try to get middle-class westerners out of their SUVs.

[I omit 7) where populations are threatened by measures that are supposedly aimed at “tackling” climate change.]

Unlike some of our contemporaries, I am not going to judge our forebears for engaging in acts that we enlightened 21st century metrosexuals find disagreeable. Some of our forebears took slaves (not mine, as far as I know; I come from countryside hayseed-chewing stock). Others set sail with their steely knives and set about slaughtering sea mammals. As I like to point out to anyone who will listen,

Poor people will kill anything that moves because it is a matter of survival.

This is why seals were clubbed to death up and down the land as soon as their lonely beaches became… not lonely beaches. This is also why entrepreneurs took ship to club seals to death further afield, or if you like, to shoot them from boats and try to net the dying animal before it had time to sink. This disgusts us now, but we live in a different world. A world where life, for now, is easy. We have electricity for light and Sainsbury’s for small packets of protein-rich food. We have the Haber process. We have phosphorus-rich minerals. We have petrochemicals.

One of the exemplars of the aforementioned pattern is our old toothy friend the walrus. A narrative (I will not say it is widespread) is that recent sightings of walruses at our low latitudes are because they are being driven south through a lack of sea ice. We had the imaginatively-named Wally, and then Freya, which may have been the one shot due to being stressed.

The swarming of walruses by curious idiots rather makes the point that remote places that they knew in prehistory are remote no longer.

Why would you want to retreat to an ice flow on the edge of the pack ice to give birth? Because places not on ice flows were not remote enough. Because in those not-remote-enough places, populations were hunted out mercilessly. They were, quite literally, driven to the ends of the Earth.

[Digressing slightly: the Mediterranean monk seal is perhaps one of the rarest seals on the planet. Uh? But the Mediterranean is a large place. Yes, but thanks to the fact that humans exist on all the shores of the Med, the monk seal was all but wiped out. It resorted to birthing its young in sea caves, where it could find them – a not unique circumstance, when it comes to men killing seals.]

There is an island in the Atlantic that I have mentioned before as a former haunt of walruses. It’s a long way south of the UK, but on the other side of the ocean. And the island is in itself sufficiently extraordinary to warrant a short digression.

Sable Island is one of those oddities that looks like an impossibility. 100 miles off the coast of Nova Scotia, you could walk across its widest point in twenty minutes, but it would take a day to walk from one end to the other (Google Earth featured image). It’s formed of sand (hence the name) and looks as if it might be part of a barrier island, but given its location, it clearly isn’t. Wiki says it was formed of a terminal moraine in the last glaciation. It doesn’t have a solid centre to hold things together – only an unusual system of sediment transport.

Naturally, as a giant sandbar in the middle of the Atlantic, Sable Island has seen its share of wrecks. Wiki says 350 vessels have come a cropper there. It was lately in the news when two dead people washed up in a life raft. Sarah Packwood and Brett Clibbery’s demise may or may not have a climate change angle. From the BBC:

In a video posted to their YouTube channel, Theros Adventures, the pair explained how their trip – dubbed the Green Odyssey – would rely on sails, solar panels, batteries and an electric engine repurposed from a car.

“We’re doing everything we can to show that you can travel without burning fossil fuels,” Mr Clibbery said in the video, posted on 12 April.

They had intended to sail from Nova Scotia to the Azores, but didn’t get very far in the Theros. The Telegraph wonders whether the yacht was top-heavy, or whether maybe the removal of the diesel engine was a mistake:

Mystery surrounds how the couple’s planned voyage turned to tragedy, with fears growing that their reliance on sail and an electric engine powered by solar panels, may have left them without back-up when things went wrong.

….

Some experts said the addition of the solar panels and battery pack will have added weight to the yacht and made it potentially unstable. There were also fears that salt water may have led to the lithium battery pack being corroded and catching fire.

Elsewhere in the article, a potential collision with a freighter is mentioned. Whatever the case, the words “Sable Island” reminded me to revisit the story of the walruses that used to call it home. There is, in truth, not much to tell: in outline, it follows the general pattern of human – sea mammal interactions that I described above. Except this one did not have a happy ending.

In those days, a large walrus was quite a prize. There were the tusks for ivory, the blubber that could be rendered down and burnt to create light, and the skin, which could be made into drive belts. The perceptive reader will note that we have alternative feedstocks for these kinds of materials now – petrochemicals.

Soon after the settlement of the New England colonies, this place became a favourite resort of fishermen for the purpose of killing morse and seals. The former are nearly exterminated, but the latter still afford, during the season, a favourite employment to the people of the Superintendent.

R. Montgomery Martin, The British Colonial Library, Vol. VI 1837

[Morse being walrus. The Superintendent lived in a house with some assistants, and they tried to rescue people whose ships ran aground.]

We take next The Natural History of the Island. For various reasons this narrow strip of sand, guarded by ever rolling surf, has been a favourite resort for various of the animal kingdom. Formerly the walrus, or sea lion, repaired to it in numbers. We read of as many as three hundred pairs of teeth collected. They have long ago all disappeared, yet even now the waves wash out from the sand the massive skull and long teeth of some old frequenter of the bars.

Lecture given to Athenaeum Society, February 1858 by J. Bernard Gilpin

There are several notices of it in Winthrop’s “Journal,” from which it appears that in the early part of the seventeenth century it was resorted to both by English and French fishermen, especially for the capture of the walrus and the seal. The former were then abundant, and were eagerly sought, their carcasses affording a large quantity of oil, their skins forming the toughest leather, and their tusks being of the best ivory and worth from three to four dollars a pair.

Sable Island, its history and phenomena, George Patterson, 1894

Well, the Sable Island walruses were hunted out, and have not returned. If they do, will it be a sign of climate change? Who knows. But the grey seals that were also present in large numbers before the hunters came have returned.

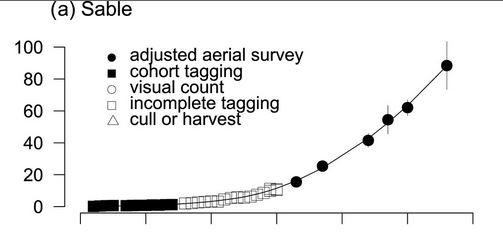

According to den Heyer et al 2020, 85,000 pups are born in a year, which is rather good going for such a small island.

And we know why they have returned, right? Because nobody kills them anymore.

This southward shift in production may reflect climate-mediated changes in population growth as well as reestablishment of colonies throughout the former range associated with increased protection.

den Heyer et al 2020

[Of course, we have to toss salt into the Devil’s eye.]

So, there we have it. A meander around a topic with a peripheral connection to climate change. Then, as we all know, everything is connected with climate change, if only you look hard enough.

Wiki again:

Being a large low-lying sandbar, Sable Island is vulnerable to sea level rise. This is further exacerbated by an ongoing increase in storm frequency and intensity caused by climate change, further eroding the island. These factors point toward Sable Island disappearing by the end of the century.

I would point to 2100 if I had to make a prediction like that, especially if I didn’t believe it. I wouldn’t be around to be proven wrong. But is it true? Two hundred years ago, Montgomery Martin thought that the island was shrinking. And bearing in mind how narrow it is, it would probably have surprised him to see it still approximately the same size today.

It is apprehended that the island is decreasing in size. The spot where the first superintendent dwelt is now more than three miles in the sea, and two fathoms of water break upon it. Although it must occasionally vary, according to the violence of storms and the action of the waters, yet it is thought that the effect of these is perceptible rather on the bars and shoals, than on the island itself ; and that it is diminished by the wind faster than it is supplied by the ocean.

R. Montgomery Martin, ibid.

This image shows an 1851 chart and a snip from a 2015 Google Earth image. The scale bars are (approximately!) the same length.

I’m perplexed by what seems to me to be an illogical claim from 2020:

This southward shift in production may reflect climate-mediated changes in population growth as well as reestablishment of colonies throughout the former range associated with increased protection.

Why would it have anything to do with climate change if colonies are being re-established throughout the former range because of increased protection?

I was also interested to note from Wikipedia that there is a substantial horse population on the island.

Thanks for educating us about an island of which I was previously completely unaware.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jit your article sends me into a funk. I knew what you were going to write. Whenever a mammal is seen as a valuable commodity or presents humans with a problem it is on a pathway to doom (only some rodents seem able to avoid this fate). Look at the forthcoming cull of badgers – to me utterly disgraceful. I recall many happy memories of watching young badgers emerging from a set.

Don’t think I should have read about the walruses this evening.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mark, because everything is climate change these days, any trend in Nature seems to attract the badge automatically. While the cessation of hunting is the most obvious reason for the southward spread of grey seals, there may be contributions from e.g. fish distribution. That is no doubt to do with (human) fishing practices. (Ongoing culls in the 20th century presumed to be at the behest of fishers who were more likely to blame competition with seals for a decline in stocks rather than their own overfishing.) But I don’t doubt that if you look hard enough, you would be able to find a “climate-related” driver of the change, whether that be ocean currents, prevailing winds, changes to do with melting ice, warmer waters, shifts in plankton bloom timings…. the list may well be as long as your arm.

Alan, I am sorry to have discombobulated you last evening. Let me offer this crumb of comfort: we are far less likely to directly and deliberately harm mammals for our own gain in these enlightened days. However, we still have numerous indirect ways of harming them, which usually are easy to fix… but of course we prefer to concentrate on trying to slow the rise of a certain trace gas!

LikeLiked by 3 people