I went looking for the origin of the government’s inane Zero-Emission Vehicle Mandate, and found myself hurtling down one rabbit hole after another. It’s interesting that even recent history becomes hard to trace these days as policy documents and web pages are superseded, departments change names, and the number of reports ramifies exponentially. Finding the bit of sweetcorn you are searching for is increasingly difficult as the size of the cess pit grows. Why was I searching for this? Well, it had to do with car manufacturers, in particular Stellantis, whingeing about the ZEV mandate. I wanted to trace how enthusiastic they were back when it was originally proposed. My memory is that the manufacturers were gung-ho for it, being preternaturally dim.

However, this little exploration does not trace that bit of history, because it ended up getting so sidetracked. The original attitude of the manufacturers to the ZEV mandate will have to wait for another day (if any commenters would care to paste in a link that might shorten my search, I would be grateful). This short discussion digs into the origin of a statistic used, or rather misused, in one of the CCC’s outputs.

The CCC put out a briefing document in 2020 entitled

The UK’s transition to electric vehicles

Actually, it was

A report by Terri Wills for the Climate Change Committee.

Terri Wills is an independent climate change consultant who worked with the CCC throughout 2020 to identify opportunities for business to deliver the UK’s Net Zero objectives

I don’t know who Terri Wills is. But I find it interesting that the government outsources its climate policies to the CCC, who outsources them to a single “independent climate change consultant.”

(I exaggerate. But only slightly.) One of the briefing note’s recommendations, as you may have gathered from the preamble, was a zero-emissions vehicle mandate. It followed hot on the heels of the CCC’s 6th Carbon Budget, the actual source of the policy recommendation, which was that:

A zero-emission vehicle mandate should be introduced, requiring car and van manufacturers to sell a rising proportion of zero-emission vehicles, reaching nearly 100% by 2030, with only a very small proportion of hybrids allowed alongside until 2035. This should strengthen incentives to sell EVs in the UK market.

Smart guys, the CCC. They think that if you ban one product, it will increase the sales of an inferior product that does the same job. Example: banning milk will increase the sales of vegan alternatives. I don’t know about you, but I would prefer to drink soya milk than have black tea/coffee. Not almond milk, which tastes like ashes. Another example: banning cheese will increase the sales of vegan alternatives.

(OK, there are limits to this. Have you tried vegan cheese?)

Minor digression begins: putting the CCC in charge of climate policy is like putting a committee of Year 7s in charge of high school lunch menu policy. As an example of the CCC’s delusional recommendations, I offer their approach to feeding the UK:

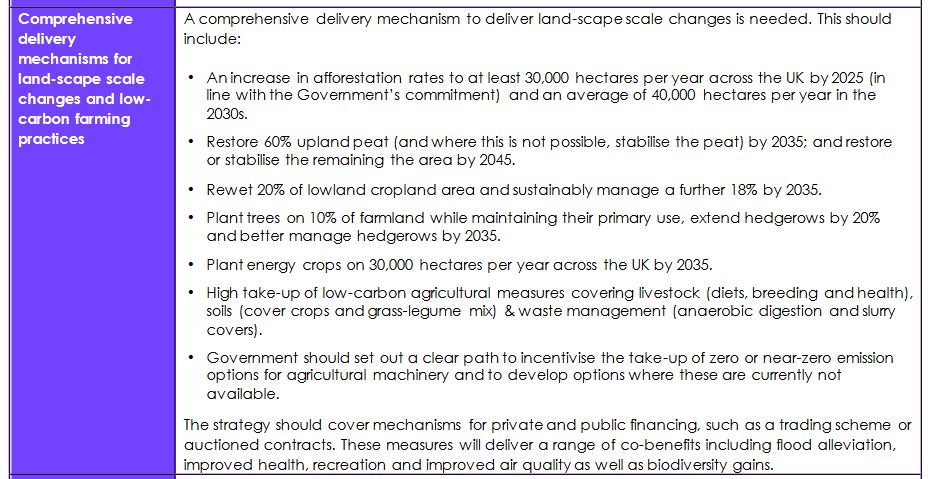

Land and greenhouse gas removals. There is [i.e. there will be under their scheme] a transformation in agriculture and the use of farmland while maintaining the same levels of food per head produced today. By 2035, 460,000 hectares of new mixed woodland are planted to remove CO2 and deliver wider environmental benefits. 260,000 hectares of farmland shifts to producing energy crops. Woodland rises from 13% of UK land today to 15% by 2035 and 18% by 2050. Peatlands are widely restored and managed sustainably.

That’s new woodland of almost the size of Norfolk, energy crops covering an area half the size of Norfolk, and they want 20% of lowland agricultural land (i.e. the lowland peats, the best farming areas) to be rewetted:

The farmed lowland peats cover 243,000 ha but that is far less than 20% of the lowland agricultural land. Let’s assume they want all of that re-wetted. This won’t necessarily mean you can’t grow crops on it, but you can safely bet that it won’t work very well if you do, and that you will have very angry farmers if you try to force them to do so. They also want another 18% to be sustainably managed, which presumably means not intensively farmed. They want 85 GW of solar PV, which going by the usual rule of thumb means 170,000 ha or 1,700 km2.

And let me just repeat…

“…while maintaining the same levels of food per head produced today…”

Turkey twizzlers for mains and crème eggs for dessert.

Minor digression ends.

Let me screech back onto the track I wanted to follow before I saw something else interesting in the weeds. One of the co-benefits of the ZEV mandate that was identified in the briefing note by the CCC via the independent climate change consultant was:

• Improved air quality. The link between EVs and air quality is clear. Air pollution is the top environmental risk to human health in the UK, and in the UK alone in 2016 was responsible for 40,000 premature deaths.

Remember, this document was produced at the end of 2020, so there was really no excuse for wheeling out this zombie statistic. My thanks go to Stew, who linked to this comprehensive explanation by Prof. Spiegelhalter in a contemporaneous comment at Notalot.

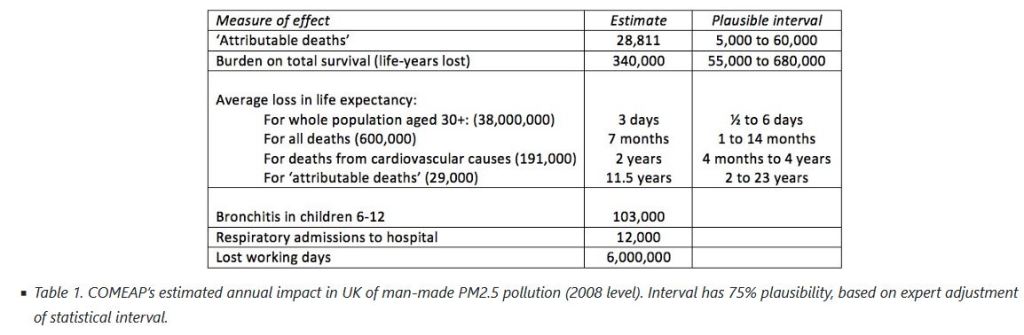

The 40,000 deaths came from a report in 2016 from the Royal College of Physicians, which took its data from a 2009 report by the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution. COMEAP’s results for the UK in turn derive from from a 2002 paper by Pope et al who calculated a risk ratio of 1.06 per 10 μg PM2.5 per cubic metre. The deaths were not deaths at all since (until lately) air pollution has never been on a death certificate. Their main role was to shorten the lives of already moribund people:

Spiegelhalter goes on to say that the WHO target is 10 μg PM2.5 per cubic metre, so that in effect there is no additional risk if you live somewhere with that average level.

One thing that is generally agreed upon is that the air is rather cleaner now than it was before. The COMEAP risk ratio was obtained for 2008 levels of PM2.5.

At the time, London was given a risk ratio of 1.03 by Spiegelhalter, based on a value of 15 μg PM2.5 per cubic metre.

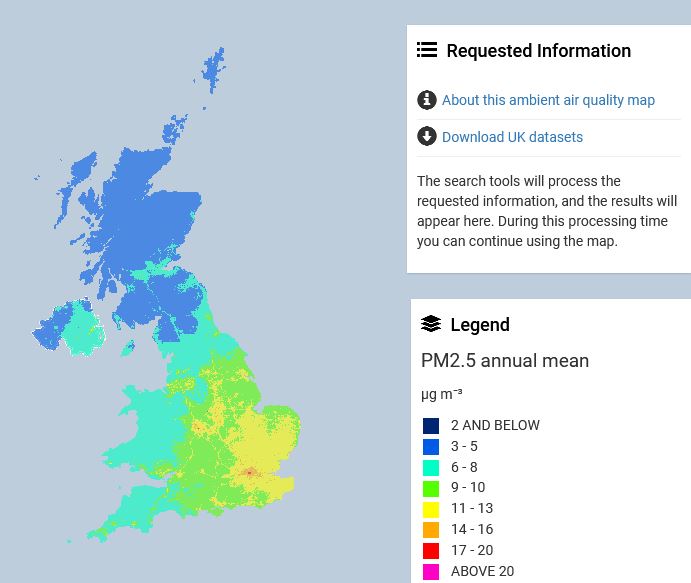

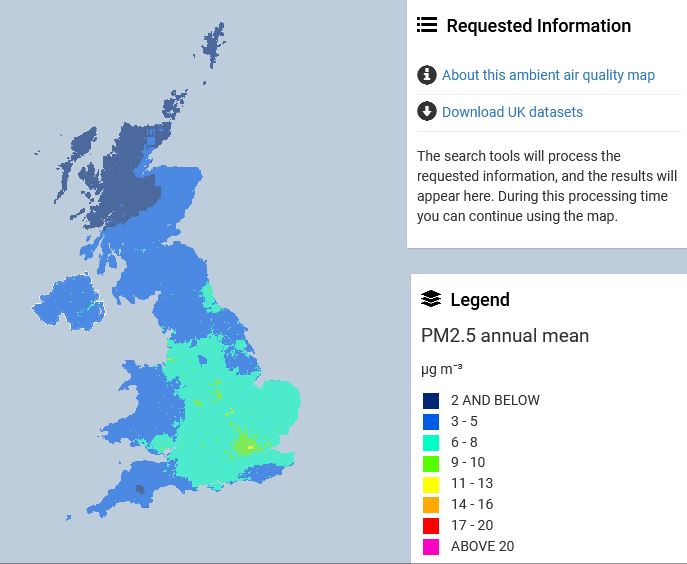

The latest map from Defra [select the pollution type and the year from the drop-down menus] looks like this:

A very small part of the UK breaches the WHO guidelines, unless they have revised them down in the interim.

Spiegelhalter says of the 1.06 risk ratio:

For a start, we can make comparisons with other aspects of lifestyle and environment by going back to the relative risk estimate of 1.06 per 10 mPM. This is very roughly, pro-rata, like an extra hour watching TV, being another 3Kg overweight, or having an extra drink.

Nevertheless, cleaning up our air is seen as a major co-benefit of the ZEV mandate by our indefatigable committee and their independent climate change consultant. I delved quite deeply in the CCC’s 6th carbon budget and in their briefing note on EV adoption. But I don’t remember them highlighting the societal costs of their ZEV mandate quite so prominently. It would probably quite useful to know how much productivity is going to be affected by long-distance drivers sitting on forecourts recharging their batteries. (The DfT thinks that “decarbonising” transport will have jobs and growth co-benefits as well as health benefits.)

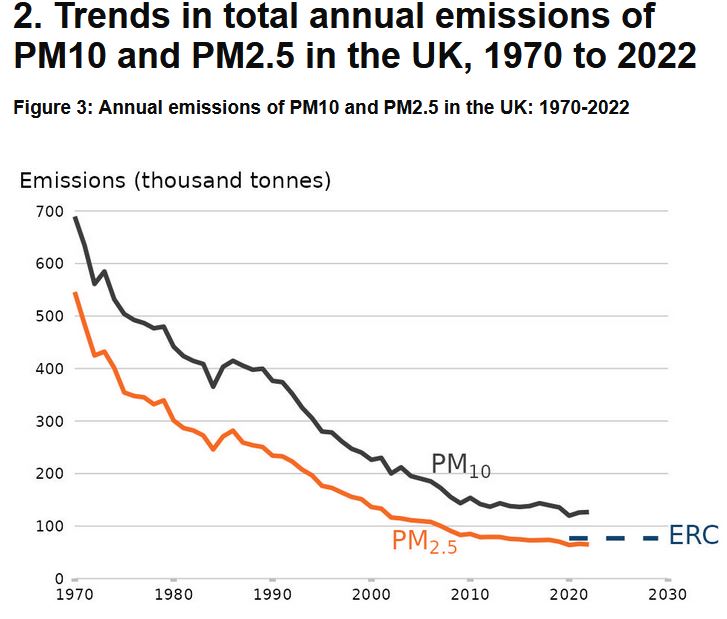

Bonus figure, showing the UK’s emissions of PM2.5 over the last 50 years:

(Of course, I’m talking to myself, since we all died in 1970, the air was that bad.)

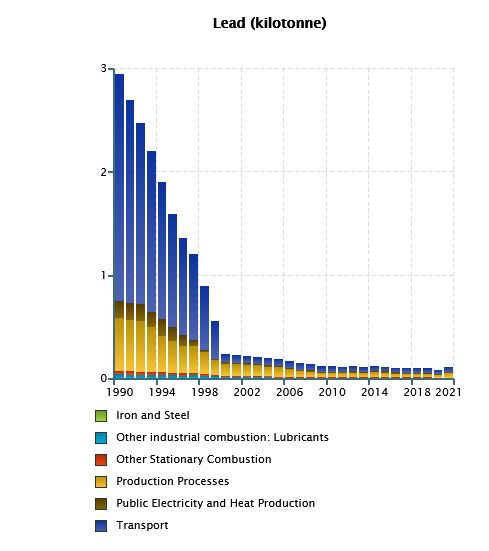

Bonus bonus figure, showing the decline in lead emissions from transport. I can only find data going back to 1990 without a deeper search, so here we are. Remember the good old days? Walking along the main road breathing in all that lead chloride?

If anyone has memories of the air before the figure begins, please regale us.

See also No Smoke Without Tyres: on the particulate matter arising from EV tyres.

Featured image: a bohemian cycling the wrong way as an example of a hoped-for future, from the DfT’s 2021 “Decarbonising Transport.”

I wouldn’t worry too much about battery vehicles – they’re on their way over the cliff of Govt sponsored calamities, along with asbestos, thalidomide and the PO horizon system

LikeLike

Jit, thanks for doing this.

I have long been opposed to politicians shunting off responsibility for decision-making to experts (Bank of England re interest rates; OBR re economic policy; CCC re policy relating to greenhouse gas emissions, energy and transport etc; SAGE re imposing house arrest on me for weeks on end, etc etc). This is for two reasons, essentially.

First, we don’t get to choose the experts, nor do we have a say in removing them, unlike politicians. They are, essentially, unaccountable.

Second, history shows that they – just like politicians and the rest of us – are capable of getting things wrong, sometimes disastrously so.

If someone screws up, with regard to pubic policy, I believe they should be accountable, and I believe that we, the electorate, should be able to express our displeasure regarding the effect their mistakes have had in reducing the quality of our lives. In short we should be able to vote them out.

It’s bad enough knowing that politicians are increasingly abdicating responsibility by contracting-out to “experts”; but to discover that highly paid “experts” are contracting-out (no doubt at our expense) to other “experts” is doubly annoying.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Mark,

It’s not only the technical competence of these experts that is the issue here. Whilst all such experts might claim an objective independence, the reality is quite different. They all have political opinions and are generally incapable of keeping them out of the equation. In fact, in most instances they appear to be highly motivated to use their expert input to game the system.

Oh but I forget, I’m a climate change denying conspiracy theorist, so I’m not supposed to know how the scientific method works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well I vividly recall the air quality (what an oxymoron) of East London in the 1950s. During the winters, which I also recall lasting longer (from November to March) and being colder, we suffered from repeated thick fogs that, when mixed with air pollution from coal-fired power stations, created thick pea-souper smogs or freezing smogs. I can still picture in my mind’s eye the sudden appearance of car headlights suddenly appearing from the gloom, even at midday, and not being able to discern the rear of the same car. I also recall my mother having to re-wash clothing covered by grime from the smog when hung out to dry.

One of the main reasons my memories are so strong is that as a boy I was asthmatic and during smogs suffered from boughts of coughing and commonly had to miss school. There were no effective remedies nor preventive measures. When I went to university in the 1960s (also East London) I don’t remember any asthma nor any severe smogs. Car pollution was still rife, but power stations had largely cleaned up.

I doubt if the pollutants were sized in the 1950s and in the 1960s it may well be that the finest grades were still being emitted but not identified, but I never noticed them, let alone suffered as a result of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for those memories Alan. My own memories of air pollution do not date from as far back, and are nowhere near as dramatic. One thing is for sure – the safer we are, the more hysterical we get about how unsafe we are. Perhaps this has to do with anxiety displacing fear.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thinking more about smogs made me realise that most of the pollution didn’t come from power stations (but some undoubtedly did) but from the belching fumes from countless individual house coal fires. It was only after the development of smokeless fuels and the banning of coal fires that smogs also disappeared. Years later many of the rows of houses, where I lived, were retrofitted with central heating and all thoughts of heating pollution became a distant memory (or mental void in my case). Central heating also dispensed with hot water bottles at night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Growing up in the north east of England in the 1960s and 1970s, coal fires were commonplace, as were cars using leaded fuel, and the air quality was poor. Things have improved beyond all recognition, and while we could no doubt improve further, the constant scare-mongering seems to me to be unwarranted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s 2024 and my neighbour a few doors down regularly burns coal on an open fire. It stinks and I often have to close my windows or come in from the garden. That’s just one fire, so I can imagine how awful it must have been with most houses burning coal as well as factories. It’s estimated that 12000 people died in 1952 as a direct result of the December Smog.

LikeLike

Jaime. I was born in East London and lived there till adulthood. We never noticed or smelt the smoke pollution from the multitudinous coal fires every winter except when it contributed to the formation of smogs. But now, in my 80s and in a semi-rural setting I am apparently sensitised and can recognize when one of my near neighbours starts even a wood fire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s probably more the case that you were desensitised to the pollution when you lived in East London Alan, because it was so ubiquitous. The air is so relatively clean nowadays that wood smoke and particularly coal smoke is very noticeable. Curiously though, I don’t object to the whiff of wood burning, but coal smoke actually makes me feel quite sick after a while.

LikeLike

Jaime J: I had the same thought, especially when I recall that smoking was ubiquitous in those days – the the home/car/office/etc.. That would have desensitised even the non-smokers.

LikeLike