Do you consider yourself to be intelligent? In your opinion, are you reasonably well-educated in scientific matters? Well let’s find out, shall we? Answer true or false to the following statements:

- All radioactivity is man-made

- Lasers work by focusing sound waves

- Electrons are smaller than atoms

I’m prepared to guess that you didn’t find this quiz too difficult, in which case you are well on the way to obtaining a high score on the Ordinary Science Intelligence (OSI) scale. Normally that would be a good thing, but the chances are that you are reading this article because there is at least one aspect of climate policy that troubles you. In which case (I am led to believe) your high OSI score has been your worst enemy. Apparently, you will have used your ‘scientific intelligence’ to justify to yourself what are actually highly anti-scientific viewpoints. You know the sort of thing I am talking about: things like questioning the true epistemic value of scientific consensus, or worrying that ostensibly objective scientific advice can be laced with political motivations. No one is saying that these are not the concerns of an intelligent individual, but there are some who think it is an intelligence that is being put to bad use, i.e. the denial of incontrovertible climate science facts. The accusation made is that you simply choose to ignore these climate truths because it suits your personal identity to do so. Your resistance is supposedly emotional, and your intellectual arguments are no more than convenient rationalisations, designed to provide a pseudo-logical justification for having your beliefs and feelings in the first place.

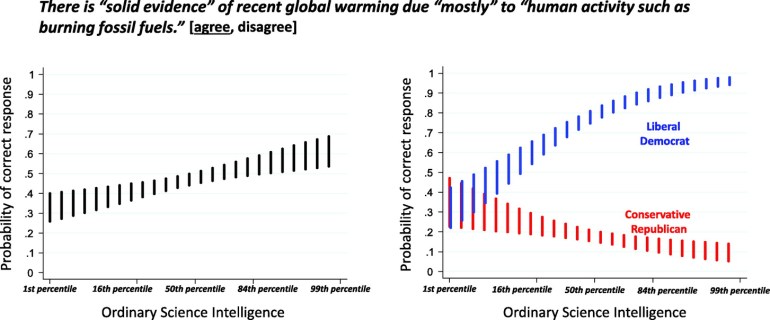

These ideas are supported by the work of Dan M. Kahan, professor of law and psychology and inventor of the OSI scale. He had invented the scale because he wanted a reliable metric that he could use to determine whether a lay person’s understanding of scientifically controversial issues is governed by a so-called information deficit, or whether something else was going on. He discovered that, in the general case, a person’s views on matters such as climate change were not strongly determined by their OSI score. However, he found that OSI was a factor when ideological leanings were taken into account. For those with left-wing liberal viewpoints, the OSI score was a strong factor determining how much the individual was likely to uncritically accept the scientific consensus; the higher the OSI, the greater the level of acceptance. However, the reverse was true of the conservative thinker; higher OSI scores corelated with higher levels of scepticism. Each group was using its scientific understanding to justify what is in fact an ideologically motivated position and, as a result, higher levels of intelligence were just leading to increased polarisation.

I’m not actually very surprised by any of this. I’ve long said that our rationality cannot be taken at face value and that we are strongly motivated to protect our values and identity. Moral outlook has a bearing on how one’s scientific understanding plays out, and emotion plays a greater role in our decision-making than we care to acknowledge. And if that were the end of Kahan’s findings I would have nothing to complain about. However, unfortunately, we are talking about a psychologist here, and so you should not be surprised to discover that there is a bias blind spot lurking in the detail. To see this, one has to examine the figure used by Kahan to illustrate his findings:

To the left you can see how, in the general case, higher OSI modestly increases agreement with the statement made. However, to the right one can see that higher OSI strongly increases agreement from the left-wing liberal group but has the opposite effect for the conservative thinker. Dan Kahan offers a number of reasons for this polarisation, suggesting in particular that where one lies on the individualistic-communistic axis of thinking, or on the hierarchical-egalitarian axis, determines how your OSI influences one’s judgment. This is all very interesting, but I don’t want to talk about that. What I want to point out is an important detail in the above figure: the y-axis is labelled ‘Probability of correct response’.

Firstly, it is relevant to say that Kahan is very likely to be a left-wing liberal (a poll shows that the left-right ratio within the profession is about 15:1). I also assume his OSI is very high. This would put him right up there at the top of the blue curve, in which case it should be no surprise that he would label the figure in the way he did. When it came to it, he couldn’t prevent his views from corrupting the analysis of the data. What should have been presented as an illustration of polarisation, with no judgment being made either way, has been turned into a graph that purports to show that right-wing intellectuals are unique in using their intellect to defend a scientifically indefensible position. In contrast, the left-wing thinker’s agreement with the statement is equated to a superior understanding of the issue. For the left wing, education has proven a good thing, but for the conservatives it turned out to be just an instrument for self-deception. Or so says the Kahan graph.

But when you look at the question asked, we are not talking about an objective issue here — we are not talking about the size of electrons. The question relates to a subjective judgment regarding whether “solid evidence” exists. When people answer true or false, they are not offering a right or wrong answer; they are declaring what they are prepared to characterise as “solid”. For example, some may say that the term “solid” is very appropriate given that the IPCC has declared the likelihood to be “high” (another term that is, however, open to interpretation). But not everyone has confidence in the reporting methodologies of the IPCC, particularly given the possibility of prosocial censorship playing a role. At the end of the day, opinions are being expressed and the graph shows a polarisation of those opinions. The graph cannot, therefore, be presented as proof that those of a particular ideological persuasion are uniquely susceptible to a cognitive failing leading to poor understanding. And yet that is precisely the interpretation Kahan’s diagram invites.

Such invitations are rarely declined; the opportunity to characterise climate scepticism as a cognitive ailment is just far too tempting for some. And so, we have academic papers such as, “Climate Change Denial as Identity Defence: Understanding Resistance Beyond Ignorance”, in which it is stated:

Climate denial is often misunderstood as ignorance, but evidence from neuroscience reveals it as identity protection.

You are welcome to read the rest of the paper if you wish, but you will search in vain for any recognition that climate advocates are just as guilty of using their intelligence to protect their identity and so their own position also has to be seriously challenged. Then, of course, The Guardian insists on getting in on the act by bemoaning how apparently intelligent people can conveniently ignore what they surely must know to be true. Incredulously, it asks of ‘climate denier meetings’:

Could an audience of experienced, intelligent people really be this blithely indifferent to the devastating impacts that unmitigated climate change will wreak on the world their progeny must inhabit?

Assuming that such ‘denier’ audiences are familiar with the concept of insuring against future calamity, it then asks:

Why then, when it comes to assessing the greatest threat the world has ever faced and when presented with the most overwhelming scientific consensus on any issue in the modern era, does this caution desert them?

And there was me thinking that the most overwhelming scientific consensus on any issue in the modern era was that electrons are smaller than atoms. Anyway, the posited sceptical lunacy on display is then explained in terms of the selective application of scientific knowledge in the pursuit of self-interest:

Short-termism and self-interest is [sic] part of the answer. A 2012 study in Nature Climate Change presented evidence of “how remarkably well-equipped ordinary individuals are to discern which stances towards scientific information secure their personal interests”.

Once again, you are welcome to read the rest of the article, but if you were hoping to find a balanced assessment of the phenomenon of motivated reasoning, you must prepare yourself for disappointment. As far as The Guardian is concerned, such maladaptive thinking is the sole preserve of the elderly, white male! That said, The Guardian is more than a little anxious to protect its sacred cows:

It is, however, deeply unfair to tar all elderly white men as reckless and egotistical; notable exceptions include the celebrated naturalist David Attenborough and the former Nasa chief Jim Hansen.

Speaking as your average reckless, egotistical, elderly, white male, I have to say that there are plenty within my demographic who are zealously supporting the idea of net zero by 2050, without so much as the slightest understanding of just how much intelligent self-deception that requires.

Of course, the weaponizing of behavioural science insights is nothing new; characters such as John Cook are making a highly successful career out of it. Actually, I struggle to think of a behavioural scientist who isn’t. The problem isn’t that research such as that undertaken by Dan Kahan is flawed; it is that it is applied in such a highly tendentious manner. I am quite prepared to concede that I apply my intelligence in defence of my values and beliefs. I just wish that those in the psychology profession were prepared to admit the same of themselves. In fact, if there has ever been a professional group that uses its intelligence to protect its own values, it must surely be the behavioural scientists. There is more than a hint of hypocrisy here, and I have to say that there is nothing more ironic than a bias blind spot that involves a professional group accusing others of being uniquely susceptible to bias blind spot.

If there were and had been no human presence on Earth, there would be no anthropogenic warming. Would our Earth, minus humans, be warming or cooling from natural climate variability? I don’t think we have any way of knowing that. I’d like to hear any science based disagreement. We can look at past warming and cooling trends and extrapolate. Depending on the length of the trend we choose, we can infer we’re in a natural warming or cooling phase. Of course, that phase might have changed over the past 100- 200 years as CO2 emissions and land use changes increased. It’s a wicked problem. If we’re in a natural warming phase, then anthropogenic warming may be very low, possibly non-existent. If we’re in a natural cooling phase, then anthropogenic warming may be very high, even over 100%. The IPCC has stated in the past that at least 50% of recent warming is anthropogenic. That’s just an educated guess, I think, and probably a good one, IMO. That leads to two more questions: First, is that inferred anthropogenic warming, at least 50% of 1.5 C degrees these past 150 years, enough of a significant threat to try and contain or reverse, and second, if it is a significant threat, then what are the best and most cost effective means to mitigate and/or adapt to the threat?

The belief that we have solid evidence about the amount of anthropogenic warming, the level and risk of that warming, and the best and most cost effective ways, if needed, to mitigate and adapt, has been promoted by many of Kahan’s (and my own) political left as “settled science”. Many on the right promote the belief that the warming threat is a hoax or scam. OSI is not a reliable method of discernment because the causes and effects of global warming are still poorly understood and contested.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Doug,

Rather than entering into too much of the scientific detail, I prefer to see the issue as a case of decision-making under uncertainty, and to ask myself whether the correct principles of decision-making have been applied. The answers one supplies to oneself are likely to be influenced by personal politics since, after all, decision-making is essentially a matter of politics. Paramount amongst the considerations is the strength of evidence upon which one would wish to base a decision. These considerations are rarely conducive to being objectively determined.

LikeLike

OSI_1.0 and its successor OSI_2.0 might be a useful scale generally for determining the scientific intelligence of people, but I believe it cannot be applied to assess climate science intelligence and most definitely not to assess climate science intelligence of left wing liberals and right wing conservatives. This is due to the nature of ‘climate science’ itself and the inherent biases of left wing liberals and right wing conservatives in relation to ‘climate science’. I think the same can be said also of some areas of medical science, in particular vaccination. Kahan says:

My bold. Because in climate science, “basic scientific facts” themselves are a subject of hot dispute between consensus believers/enforcers and climate change sceptics. In particular, what sceptics call ’empirical information’, empirical data and empirical facts is often very much at odds with what those who uncritically accept climate change science judge to be scientific facts (and in point of fact, climate consensus afficianados rarely mention the term ’empirical’, what with its unfavourable association with ’empire’ and all). How so? Because climate science is largely model output, not empirical data, and even the empirical data itself which is used to validate the models often is sparse and of poor quality. It tends to be the case that, when it comes to climate science, left wing intellectuals place far more value upon computer generated ‘data’ than do right wing intellectuals and conversely, right wing intellectuals place far more value upon empirical ‘hard’ data than do left wing intellectuals. That’s why Kahan’s OSI fundamentally breaks down when he tries to apply it to this particular field and why it tells us basically nothing useful other than that which is blindingly obvious. It’s why Kahan himself makes the stupid mistake of labelling his vertical axis as correct, in the mistaken belief that the probabilistic attribution of recent global warming entirely to man-made GHGs is an established, empirical fact. It is not. That’s not me protecting or asserting my identity as a right winger. Probabilistic attribution using climate models really does not qualify for the status of “basic scientific fact”.

LikeLiked by 7 people

Jaime,

Indeed. It is an objective fact that the climate science community considers the evidence to be solid (albeit that isn’t the word used by the IPCC). It is also an objective fact that those who do not share that position are said to be antiscientific. That’s as far as objectivity goes on this matter.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t know where all this leaves me – a one-time Labour Party activist with no time for Trump or Farage, Starmer or Miliband, socially liberal but economically fairly right-wing, and (I hope) reasonably intelligent, a white man in my early 60s, once a daily reader of the Guardian (which I regarded as representing my views, but which I now find antithetical save for occasional flashes of its former brilliance and decency). Like John, I cheerfully concede that I “apply my intelligence in defence of my values and beliefs.” Like John, I never cease to be amused and bemused by the blind spot of those true climate believers who don’t seem to recognise their own biases. We all have them, true believers and sceptics alike. Sceptics recognise that, but believers don’t seem to. I prefer to be amused, rather than angered, by it. The worm is turning, and that’s enough for me – for now.

LikeLiked by 4 people

“Mostly” due to human activity? I would probably hover over a value of about 50%, if asked. That is my honest opinion of the state of reality. So I could easily fall into either camp, depending on which way the wind was blowing. However, if I knew I was being tested by a liberal professor, I think I’d make sure I was on the side of the devils, out of bloody-mindedness.

Quite a choice quote, that. Score zero for the first assertion, and negative zero for the second. No-one serious believes those things. I prefer to think the Guardian is lying for Gaia than that it is really that stupid.

PS. Those error bars were surprisingly tight.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for another informative article, and thanks for that 2017 The Guardian link back.

Love the article title – “Climate deniers want to protect the status quo that made them rich”.

The irony.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a point of further interest, Dan Kahan has been involved in further research in which it is claimed that motivated reasoning, whilst exacerbated by OSI, is mitigated within individuals exhibiting high scores on a so-called Scientific Curiosity Scale (SCS):

Science Curiosity and Political Information Processing

I will withhold my opinions for the time being, to give others a chance to express their own opinions of this research. Suffice it to say, I find aspects of it somewhat unconvincing — or at least I am less than convinced by the interpretation of results offered by the researchers.

LikeLike

Like all surveys of public opinion, the results show which of the media narratives has been most persuasive. It is also true that people whose values are conservative are more prone to question claims that lead to increasing government oversight over individual choices, while the left (formerly liberal) are predisposed to trust government solutions. On this particular survey topic, note how Canadians responded:

The only place where a majority agreed (slightly) is where many of the ruling elite live in Montreal and nearby Laurentians. The Truedeau Liberals found a way to hide this finding and twist the report to say it supports a carbon tax. Like beauty, it seems truth is in the eye of the beholder.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For anyone interested, I deconstructed the survey at the time:

https://rclutz.com/2016/02/25/uncensored-canadians-view-global-warming/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, this is the deal with the Kahan paper I linked to earlier today. As with the paper featured in my article, it is a paper that claims to illustrate how agreement with the statement that solid evidence exists for AGW is influenced by a particular cognitive state; in this case scientific curiosity (SCS) rather than ordinary scientific intelligence (OSI). The claim is that the reason why sceptics are the way they are is because they lack scientific curiosity.

The authors claim to have discovered that, unlike OSI, the level of SCS serves to overcome motivated reasoning rather than facilitate it. That is the reason given for why conservative thinkers agree more with the statement when they have higher SCS (with high OSI, the opposite was true). However, the paper concedes that OSI and SCS are correlated (r=0.26) so higher SCS also implies higher OSI (as one might have expected anyway). So, the graph showing how SCS increases the level of agreement for the conservative thinker is taking into account the mitigating influence of the implied higher OSI. Even so, the positive influence of SCS on the conservative thinker is so great that it turns an otherwise reduction in agreement into an increase in agreement, implying that the motivated reasoning has, on balance, been overcome!

When one looks at the graph for the liberal thinker, there has to be a similar influence. A higher SCS would reduce levels of motivated thinking, but the impact would be mitigated by the fact that higher SCS also implies a higher OSI.

The puzzle is that, when you look at the graph showing how SCS influences levels of agreement with the statement made, the net effects of the suitably mitigated SCS are identical for both conservative and liberal thinkers, i.e. the impact of SCS on levels of agreement with the statement made are identical in both cases. This strikes me as a remarkable coincidence. It’s as though r=0.26 was just the right degree of correlation between OSI and SCS to produce a net impact that is identical for both groups.

I don’t trust such coincidences. I think a much more likely explanation is this: The graph showing higher levels of agreement under the influence of SCS is actually showing the influence of a confounder; one that correlates well with SCS but not very well with OSI. What could that confounder be? Answers on a postcard please, but perhaps those with high SCS just tend to get more exposed to the dominant narrative, and dominant narratives tend to…well, dominate.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think the confounder is that leftists (formerly liberal) have a ton of social support for taking the “consensus” view, while conservatives are wary of identifying as “deniers.”

LikeLike

r=0.26 is minimal. A scatter plot of two variables with such a correlation would like like the distribution of plums in a plum pudding. I would be interested to learn how SCS correlates with a CS score across other areas, perhaps where satisfying that curiosity comes at less effort. A more generalised score could be revealing.

LikeLike

Max,

You are right, perhaps I am overstating the significance of what is actually a very modest level of correlation between SCS and OSI (a low level that I actually find very surprising). The fact remains that the impact of SCS in overcoming the detrimental effect that high OSI has in the conservative thinker, and independently its impact in overcoming the OSI of the liberal thinker, creates a net effect that exactly correlates between the two groups. I find this coincidence to be somewhat puzzling.

LikeLike

Perhaps it was r-squared which would be the more statistically respectable metric for quantifying how much of the variance of the Y variable is explained by X. I would like to see people marked along a “niceness” or “bonne pensee” scale, quantifying their proclivity towards expressing views that elicit praise from others on the expressor. “Expressing” not “holding”. Maybe just a variant of “virtue signalling”.

LikeLike

Max,

I don’t think academia is short of papers claiming to correlate certain undesirable personality traits with maladaptive thinking on climate change, by which is meant thinking that doesn’t uncritically accept the scientific consensus. No matter what, the studies will purport to have identified the source of an irrationality that psychologist (i.e. the liberal left leaning) have found in the sceptic (i.e. the right-leaning). I don’t think anyone within that identity-protecting group is going to take up your challenge of understanding how less than desirable traits can be responsible for enthusiastic climate action advocacy.

LikeLike

Max,

Incidentally, this is how Kahan et al explained their results:

“Because science curiosity plays a role in promoting science comprehension too (Figure 6), it would stand to reason that it would be associated with the enlargement of polarization. It didn’t; on the contrary, with respect to the most contested risks, SCS counteracted the MS2R effect associated with science comprehension…The discrepancy between SCS and OSI on subjects’ climate-change risk perceptions begs an explanation. A plausible one is that individuals who are higher in science curiosity, in order to satisfy their appetite to experience wonder and surprise, expose themselves more readily to information that is contrary to their political predispositions, a form of engagement with information generally contrary to PMR [politically motivated reasoning].”

As I have said above, what it will expose them to is a lot of PR promoting the dominant narrative. It’s not that the information is contrary to their political reasoning, it’s that it is information that has been labelled as the ‘correct response’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That word “correct” in the vertical axis label sticks out like a sore thumb, an embarrassment in the context of a paper purporting to be about sources of an attitude where the author should at least pretend to stand above taking a personal position. It would be interesting to know if Kahan’s unprofessional mislabelling of the vertical axis arose from his personal self censoring, a requirement of his institution, an afterthought conditioned by his need for promotion, or maybe even an imposition from the journal editor who might have been alert to the danger of the paper providing grist to the sceptics mill.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Max,

I suspect Kahan’s labelling reflects an attitude prevalent within his profession. I don’t think he needed any encouragement. The presumption that the sceptical position is incorrect would come naturally to him. It’s what anyone who sits on the top of the blue curve would do.

LikeLike

Here is an article written by Kahan that claims he has shown that climate science literacy is unrelated to public acceptance of human-caused global warming. In fact, the more climate science literate people are, the more likely they are to express highly polarized views:

https://law.yale.edu/yls-today/news/climate-science-literacy-unrelated-public-acceptance-human-caused-global-warming

I mention this now because it would seem to debunk Kahan’s explanation for why higher scientific curiosity (SCS) leads to lower levels of polarisation. If you recall, Kahan said higher levels of SCS leads individuals to “expose themselves more readily to information that is contrary to their political predispositions, a form of engagement with information generally contrary to PMR”. Now he is saying that how well-informed one might be has no bearing.

One day, Kahan will wake up to the fact that scientific understanding isn’t the issue. What matters more is the individual’s tolerance to uncertainty and ambiguity when making decisions under uncertainty.

He might also learn something by inventing a scale that measures literacy in matters of risk management, uncertainty analysis and decision theory, and then see how that correlates with how people think about AGW. Except, a psychologist is the last person on Earth I would trust to create such a scale.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Andy West, in his book “the. Grip of Culture” acknowledges his debt to Kahan, but suggests that the reliability of his analysis is limited to the USA, because of the unique binary nature of US politics. His analysis of the complex & self-contradictory nature of the relation between belief in Climate Catastrophe and religiosity works for 30 odd societies, but not the US.

I hope I’ve got that right. I need to reread Andy’s book to be sure. And so do you all, if you haven’t already. It’s downloadable free here

https://thegwpf.org/content/uploads/2023/07/West-Catastrophe-Culture6by9-v28.pdf

I’d argue that Kahan asks the wrong question to get to the conclusions he draws. Instead of a straight question: “Do you agree/disagree that…” (followed by whatever belief you want to measure: – “global warming is real/man-made/concerning/fatal” etc.) he asks his informants to agree/disagree that :

“There is solid evidence of recent global warming due mostly to human activity such as burning fossil fuels.”

Note that stating that “there is evidence” and it is “solid” is already two stages away from the statement about the core belief in man-made global warming, which is itself hedged round with the provisos that it is recent (we’re not talking about natural variability or previous, unexplained warming periods) and that it only has to be “mostly” man-made.

There is evidence for all sorts of things that may or may not be true. In most interesting situations, there is evidence on both sides of the question. In a legal case, if there was not evidence on both sides, the case would either be closed with a simple guilty plea, or it wouldn’t even come to court.

Among the many reasons, to do with psychology, political belief, social position or who knows what, which might lead one to agree or disagree with Kahan’s question, is suspicion of complex questions that seem to be laying a trap, rather than simply asking for an opinion.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Geof,

I quite agree. The question is horribly layered and seems designed more to discern how certain groups might choose their words, rather than how close they are to being ‘correct’.

LikeLike

John

“The question .. seems designed more to discern how certain groups might choose their word..”

It’s curious how the word “curious” has two antithetical meanings. I’m “scientifically curious,” but I’d hate to be described as “curious, scientifically.”

LikeLike

Looking at the global warming chart, is there an alternative (or just a better) explanation for why Ordinary Science Intelligence (OSI) of left-Liberals (LDs) increases, and Conservative Republicans (CRs) decreases, other than ideology?

Imagine that Kahan’s findings were the result of well-conducted research. Preferably, groups of 100+ LDs and CRs are sat down in a room to be tested. They answer a questionnaire on science subjects and one or more on global warming. Then they are given additional “facts” that will make up for some of the information deficits they may have, followed by a re-test. What sort of information might they be given to prompt a correct response prior to July 2015, when the paper was submitted?

The statement to agree/disagree with was

What are the titbits of “solid evidence” that could have been used as prompts towards getting the correct answer in months before July 2015? I do not believe such evidence existed. But there are three things were available.

Less than two years before IPCC AR5 WG1 was published with statements like

Doran and Zimmerman 2010 asked two questions

Of 3046 responses, the authors reduced them to 79 publishing climate scientists, of whom 77 (97%) said yes to the second question.

This, and similar 97% consensus surveys, featured (without direct reference) in the 2011 Debunking Handbook by Lewandowsky and Cook, as an example of how to counter climate misinformation. There, they stated,

On the Conservative Republican side, many are bible-reading Christians. They will have been in study groups and listened to sermons to understand biblical texts. They look at the text to understand what is actually being stated, not what might be apparent on a first, cursory reading.

So, given titbits of information based on the above, they will read again.

They are being asked to agree/disagree on whether there is “solid evidence” for recent global warming being, “mostly” human-caused. Not on whether recent global warming is “mostly” human-caused. The CRs would have been expecting “solid evidence”, for recent warming being greater than 50% human-caused. Instead, they got belief statements, often based on dodgy surveys or misinterpretations of those surveys. The more they learn, the more impenetrable much. If this is what CRs picked up, the question is then why do LDs not assess come to the same conclusion?

LikeLiked by 1 person