When the BBC was taken to a secret location in Snowdonia to be shown a rare plant, I rather assumed there was going to be a climate angle to the story. Well, there was.

The first proof of this was that the reporter was one Justin Rowlatt. He gave the location in broad terms as somewhere north of Yr Wyddfa. Moody shots of trudging along a bleak shoreline and up a rocky hill followed.

The location of the plant, he said, was top secret, because there were only 7 examples left in Wales. The plants are “relics of the Ice Age that just love cold and wet conditions.”

The trouble, he went on, is that even on the Welsh mountains, the weather has continued to get hotter (sic) and drier (he was drenched from head to foot). (He did add “in spring and summer.”)

The plant, we were informed, is the tufted saxifrage, one of the “jewels of Snowdonia.”

Then it was time for a soundbite from the expert, in this case the National Trust Partnership Officer.

They like cold weather, [but] we’re getting extreme climates now, dry, warm summers, also mild and warm winters as well… they’re on the very edge of their habitable range in the UK in Eryri anyway, so if these go because of climate change, it’s almost like the canary in the coalmine and signifying what’s next. So it should be an alarm bell for us all really.

With this incoherent warning the report ended, and although there is a longer version, I haven’t watched it.

So, there you have it, an open-and-shut case of a plant in climate peril thanks to modern civilisation.

Or is it?

First of all, we might note that the National Trust has a narrative they want to sell us, so we should be cautious about taking this report at face value. However, to begin with, the National Trust guy said something plainly true: that these plants are “on the very edge of their habitable range in the UK in Eryri anyway.”

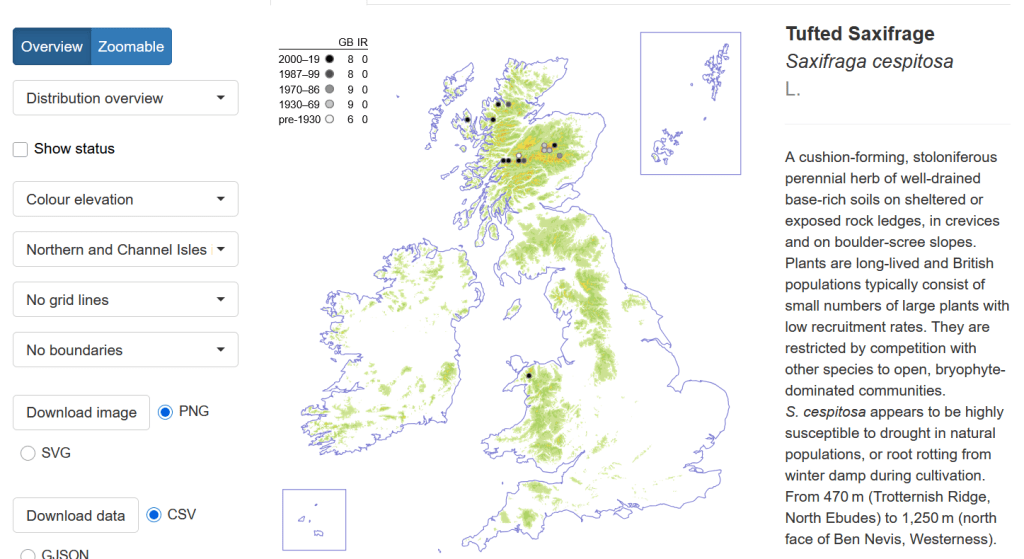

This can be confirmed with reference to the UK’s online plant atlas:

Let me just cut’n’paste the commentary, in case it’s unreadable:

A cushion-forming, stoloniferous perennial herb of well-drained base-rich soils on sheltered or exposed rock ledges, in crevices and on boulder-scree slopes. Plants are long-lived and British populations typically consist of small numbers of large plants with low recruitment rates. They are restricted by competition with other species to open, bryophyte-dominated communities. S. cespitosa appears to be highly susceptible to drought in natural populations, or root rotting from winter damp during cultivation. From 470 m (Trotternish Ridge, North Ebudes) to 1,250 m (north face of Ben Nevis, Westerness).

According to this description, tufted saxifrages have a set of requirements that is difficult to find. On the one hand, as many mountain plants do, they like base-rich conditions, but most parts of most UK mountains are on acid soils. They like good drainage, but on the other hand, abhor drought. They are the size of moss, and live amongst moss in open communities, showing that they cannot cope with shading.

Now, we’re going to wind back through time, to the last Ice Age, when life for British tufted saxifrages was easier, and when none of the species we can see by looking out of the window were tough enough to live here. Then, what are now described as Arctic plants grew in abundance on the boulder clay and pulverised rock shovelled southwards by vast sheets of ice. The plant community was open – there were no trees. It was base-rich, and there was little in the way of developed soil. As the climate warmed, this habitat was replaced over slow aeons, giving way to a dense wildwood. The Arctic plants could only survive at higher elevations, where there was no competition from more vigorous, yet less cold-tolerant, species. The survivors lingered on north-facing rock faces, but eventually most of these Arctic species were lost to the country, even the mountainous north.

It’s at times like these that I pick up “Mountains and Moorlands” by W. H. Pearsall (1950), to see what that learned gentleman had to say, back when no time was given to the thought that carbon dioxide might be a dangerous pollutant. What does Pearsall have to say? I’ll have to read it first, then I’ll tell you.

Thus the montane flora is evidently one which depends on an adequate supply of lime and other bases, and its restriction to newly exposed and open sites must be partly because they offer new soils with an adequate supply of the necessary minerals as well as an opportunity for colonisation. From the point of view thus emphasised, the montane plants in Britain must be the remains of a vanishing flora, for on account of the humidity of the British mountain climate, leaching and peat accumulation must both be continually reducing to a minimum the possible sites for montane species. Further, the restriction of many of these species to rock-ledges and other inaccessible places is an indication that their range has been greatly diminished by the great extension of sheep-grazing.

A description of the plant’s habitat on Svalbard is informative:

Confined to dry or only slightly or temporarily moist sites, in heaths and early snowbeds, on ridges, river terraces and bars, and in scree and on cliffs, especially bird cliff meadows where the plants may become very large. Substrates are mostly sand, gravel or coarser kinds, because silt and clay retain too much water for this xerophilous species. Probably indifferent as to soil reaction (pH).

(A bird cliff meadow is the vegetation developing at the foot of a cliff where seabirds nest, which is greatly enriched by guano.)

This is a very cold-hardy plant that is far out of its suitable climatic envelope in the UK. It lives for a long time, and probably reproduces mainly vegetatively, i.e. new plants arising from seed are rare. The same clump probably persists for decades, but inevitably something bad happens, and it dies. That may well be drought, for a plant that, if the BBC report is anything to go by, is reduced to growing in a crack in a boulder.* The population appears to be on a long and slow decline to (local) extinction, with or without climate change. It will do just fine in the actual Arctic, where it is adapted to the conditions.

However, climate change is clearly hunting this plant down in Wales.

That is why the BBC must keep its location a secret: in case climate change finds out where it is.

/message ends

*You may have a bonus point if you can guess what the name “saxifrage” means, or is derived from.

Link to BBC report (time limited).

Fingers crossed that climate change doesn’t find it.

* From the Latin: ‘saxum’ (rock) and ‘frangere’ (break).

LikeLiked by 3 people

There you go again , using facts to demonstrate that the BBC is again pushing a dishonest narrative.

Still, the shameless propaganda at the BBC and the Guardian give us plenty to write about here. 😊

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks for this informative post Jit. As noted by Robin, the name Saxifraga means breaker of rocks but the origin refers to supposed medicinal treatment of kidney stones rather than growing in rock crevices. The name dates back to Dioscorides, the writer on medical botany in the first century AD. The sole species to which the name was attached was Saxifraga granulata which is widespread in Europe and grows in grassland, not rock crevices. The small bulbils found at the base of the stem of Saxifraga granulata have a superficial resemblance to kidney stones and also the leaves are kidney shaped. The doctrine of signatures taught that a plant of medicinal value bears in external form some indication of the sphere of its efficacy (Saxifrages of Europe: Webb and Gornall).

I believe the location of Saxifraga cespitosa in Snowdonia is at the head of Cwm Idwal in the huge gully known as the Devil’s Kitchen (Twll Du). This is a relatively well-known location of botanical interest. Saxifraga oppositifolia, another circumpolar arctic-alpine plant also grows in this gully and has very attractive pink-purple flowers. Both plants require cool moist locations that are well-drained. However, I would think the ubiquitous sheep in Snowdonia are more of a threat to these saxifrages than climate change.

I have grown both Saxifraga cespitosa and Saxifraga oppositifolia in the garden and have had much more success with the latter plant.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thank you for the equally informative reply, potentilla. I had no idea that the connection was as you describe, though knew the meaning that Robin gave. Tomorrow I will have a look in Flora Britannica to see what that says.

I’m sure you are correct in describing the “secret” location. Pearsall mentions a location above Llyn Idwal.

LikeLike

Beautifully written as ever Jit. I do feel you were very kind in your description of the National Trust spokesperson. Personally I hate the NT with a passion as they appear to have been taken over by extreme activists. Climate change disinformation runs through their entire output. When investigating the Malham Tarn weather station I came across the NT’s reasoning for why an old building on the site collapsed – you guessed it, climate change. Couldn’t possibly have been anything else!

https://www.cravenherald.co.uk/news/19139629.climate-change-can-affect-buildings/

I admit to, somewhat stridently, referring to these sorts of attitudes as a “sickness” but really the number of issues falsely attributed to Climate change by the likes of the NT is rising to almost biblical proportions …….as any religion should.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ray S, quite! Try this:

https://cliscep.com/2022/07/14/climate-change-in-stirling/

LikeLiked by 1 person