“Drones join battle against eight-toothed beetle threatening forests”

So wrote the BBC a couple of days ago. As an ecologist with a special interest in crunchy invertebrates the size of peppercorns, this was a disappointing headline. Replace “eight-toothed” with “bark” and you have a better start. [It does have eight teeth, but not for chewing; see below.]

This was always going to have a climate angle – but as usual our friends at the BBC miss the important background, and leave us hardly any better informed than when we started. This is a shame, because the story would have been a great opportunity to educate the public about the relationship between the beetles and the trees. Of course, the BBC writers are not specialists, and do not have time to dig beneath what they are being told by press release. Nevertheless, it’s a chance missed, and another case of reader beware: Gell-Mann Amnesia awaits on the next story you read.

The tale was of how a forest pest was colonising south-east Britain, and the arsenal of weapons being used against it, including…

…sniffer dogs, drones and nuclear waste models

It is said that the beetles have been eradicated from the south east thanks to these strenuous efforts.

The climate angle:

But climate change could make the job even harder in the future.

You already know why: drier summers, milder winters.

The spruce bark beetle, or Ips typographus, has been munching its way through the conifer trees of Europe for decades, leaving behind a trail of destruction.

Try hundreds, or thousands, of years, not decades. “Trail of destruction” is a nonsensical way of putting the results, suggesting that they leave a barren wasteland in their wake. Of course, they don’t. Think of it this way: if you destroy a human structure, it is permanently destroyed unless a human rebuilds it. If you destroy a tree, or a thousand trees, the forest grows back.

When trees are infested with a few thousand beetles they can cope, using resin to flush the beetles out.

Upon infestation in these numbers, the tree is dead.

“Their populations can build to a point where they can overcome the tree defences – there are millions, billions of beetles,” explained Dr Max Blake, head of tree health at the UK government’s Forest Research.

Billions of brown boring beetles! But he means in a forest, not an individual tree.

Since the beetle took hold in Norway over a decade ago…

It has been present since the last Ice Age relented. There just happens to be a recent outbreak.

I’m going to stop putting in quotes there, but rest assured, there are another dozen that could be quibbled with.

The Actual Facts

The European Spruce Bark Beetle, Ips typographus, as its name suggests, comes from Europe, and lives under spruce bark. It has an interesting way of overcoming the natural defences of a host tree. Trees exude resin when damaged, and this kills beetles. Under stressed conditions, the resin production is insufficient, and the beetles get a foothold. They release pheromones, which nearby beetles home in on. Emphasis here on nearby: they are not flying from the Ardennes to Kent on the promise of a 2 a.m. kebab. The beetles infect the tree with fungus. When the bark is effectively “ringed,” the tree has had it. By concentrating on one or few trees, the beetles can overcome the tree’s defences; if they all attacked different trees, maybe none would be successful.

The tree involved is Sitka spruce. As its name suggests, it is not a native of Kent, or even of Caledonian forest. It is native of the Pacific coast, and the fog belt there. A particular stronghold is the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State. It was introduced to the UK in 1831, as a timber tree, because of its incredibly rapid growth. [You would be unwise to use it as a Christmas tree, as the needles are quite pointy.]

In fact, there are no native spruces in the UK. The Norway spruce was native here before the last glaciation, but never made it back across the land bridge. It was introduced here in about 1500, first for novelty reasons, and then for forestry.

The upshot is that Ips typographus is not native here either. So we are talking about an alien-on-alien war, which we only care about because one of the aliens is a forest crop, and we don’t want it to die before we have time to kill it ourselves.

Forest Research’s entomologists were shocked to find spruce in Kent infested with Ips in 2018, despite checks at the port to intercept infested timber. The discovery meant a meticulous search of 4500 ha of forestry, the use of sniffer dogs, drones, nuclear fallout models, AI-scanned beetle traps, etc.

Now, I want you to conjure two images in your mind: one vision is of Kent, and the other is of the fog belt of the Pacific Coast. One is the misty home of Sitka spruce that reach 80 m, and the other is one of many places it has been planted by hopeful foresters.

Here’s how Hopkinson described the forest of the Queen Charlotte Islands after his visit in 1931:

The luxuriant growth of vegetation in the Queen Charlotte Islands is most striking. The forests are a jungle and to traverse them it is necessary in many places to cut one’s way through an undergrowth composed of such plants as red huckleberry, tall bilberry, thimbleberry, salmonberry, salal, and devil’s club growing eight or ten feet in height, not to mention young Sitka spruce and hemlock, springing up densely all around. Moss covers the ground and fallen trees. Beautiful ferns abound. Lichen hangs from the trees. On every side there is evidence of abundant moisture and a mild climate.

Hopkinson 1931, p.29

Now, I would like you to contrast that with your mental image of a uniform block of Sitka spruce poles with nothing under them but a brown carpet of needles, in one of the warmest and driest parts of the UK. Where would Sitka spruce thrive best?

This is how the Slovakian forestpests.eu describe the most susceptible trees:

Most at risk are spruce stands aged 60 plus, affected by wind and snowbreak damage or weakened by drought.

Of course, these are mostly referring to the European spruces that evolved with I. typographus, not Sitka. But the inference is obvious: Sitka spruce is not suited for Kent, as it’s too dry there. Drought-stressed trees cannot produce enough resin to fight off the bark beetles, and end up succumbing. With or without climate change, Kent is not the place to grow Sitka spruce.

You can go back a long way and find stories about Ips. In Sweden, there was a serious outbreak in the early 1930s following three severe storms in 1931 and 1932:

The catastrophe which laid waste the pine and spruce forests of central and southern Sweden was effected by three storms which swept that country in July and December 1931 and February 1932.

Chrystal, 1935

After the storms, the region’s spruces were attacked by Ips. A population survey of one area in Uppland found 1.3 million Ips per hectare. In other words: this stuff is not new, even if it is new to the UK. Is it new to the UK? Old beetle books by the eminences of the day, usually clergymen, make reference to records of I. typographus in Britain. It is stated to be rare, and in very old works is found under a different genus (Tomicus). Perhaps these records are of chance introductions, and the species was never established.

Naturally it is more likely to find fertile ground when vast quantities of planting are undertaken from 1900 onwards. A useful analogy is that of a fire, which burns out if there is no flammable material nearby. When a forest pest is surrounded by stands of its favourite food, it often thrives.

So there we have it: a tree threatened by climate change, and needing drones and dogs and human surveyors to protect it? Or a tree planted in the wrong place, and growing under semi-permanent stress?

Sitka spruce will do well in the wetter parts of the UK: Monumental Trees reports on one by Loch Awe, with a height of 60 m and a girth of 4 m, achieved in 110 years of growth. [I saw these trees thirty years ago, and they were mighty then. I have not seen the original giants on the Pacific coast, which I would really like to do.]

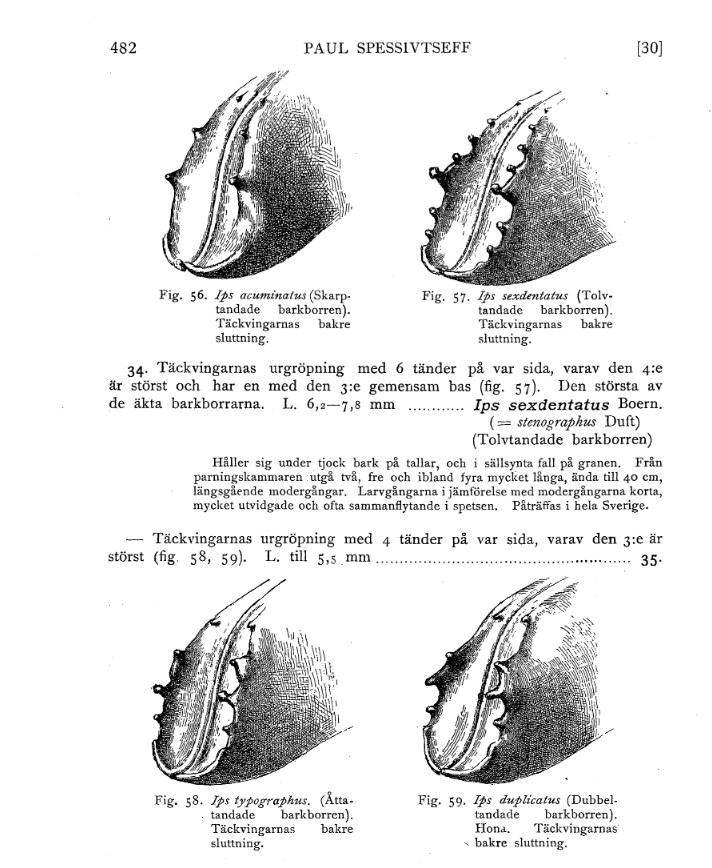

Oh, the eight teeth? As mentioned, they are not used for chewing. Rather, they adorn the elytral declivity (the back end, for non-aficionados. I presume they are used to backwards-push frass out of the borings). Here is page from a 100-year-old monograph on bark beetles “barkborrar” by Paul Spessivtseff:

Spot the eight-toothed bark beetle.

References:

Chrystal, R. Neil (1935). Bark-beetle outbreaks and their control: a review of some recent literature. Forestry IX, 124-131 [Archive.org]

A. D. Hopkinson (1931). A visit to Queen Charlotte Islands. Empire Forestry Journal, Vol. 10, No. 1, 20-36. [JStor]

Spessivtseff, P. (1922). Bestämningstabell över svenska barkborrar. Meddelanden från Statens skogsförsöksanstalt. [Google Scholar]

The featured image is from Rev. Canon Fowler’s 1891 masterpiece of beetles, The Coleoptera of the British Islands, Volume 5, Plate 179. Ips typographus is number 10, if the numbers are readable. If you really want to read it, you can find all 5 volumes on Archive.org.

Perhaps a link to the BBC article might have been helpful. It’s here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the education, most enlightening.

I see that Justin Rowlatt co-authored the BBC piece. I assume that explains the two obligatory references within it to climate change.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Whenever I read these types of articles about the spread of species “due to Climate Change” I look up their existing range and climates that they already thrive in. Clearly Ips typographus thrives in climates far wider ranging than the UK’s, so Justin Rowlatts compulsory and nonsensical inclusion of climate change is a load of twaddle.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“The climate angle:

But climate change could make the job even harder in the future.

You already know why: drier summers, milder winters.”

Of course the blighters have only recently been (re-)discovered because of climate change!

“UK Weather: Met Office Predict Wet Summers For The Next 10 Years”

PA/The Huffington Post UK. 19/06/2013

https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2013/06/19/uk-weather-met-office-wet-summers-decade-_n_3463853.html

“Met Office: Arctic sea-ice loss linked to colder, drier UK winters”

The Graun, Wed 14 Mar 2012 16.59 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/mar/14/met-office-arctic-sea-ice-loss-winter

LikeLiked by 3 people

Even the Spruce Bark Beetle subject to those ASSumptions.

LikeLike

How very interesting… I hate Sitka, as we have swathes of it here already in the Borders, and vast new plantings going on by institutions that are buying up hill land all over Scotland to plant trees and harvest the subsidies – all in the name of “fighting climate change”. Being non native, it is a poor host for insects, and therefore birds — apart from the odd raptor. The average scheme has a token 5-10% planing of “native species” and then huge areas of sitka. This is going to drastically change our landscapes — and their ecologies. I’m afraid our areas are too wet for the trees to suffer permanent stress — but this summer has been very dry so I live in hope ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Various sites are running the piece by the BBC on ‘Stressed Trees’ claiming doom and gloom for our trees. We have 3 Sycamores, 1 Apple and a huge Laurel bush in the garden, they have grown like mad in the last 2 to 3 years and now becoming a nuisance. So much for stress.

LikeLiked by 2 people

James, I have been meaning to write a diatribe about this story, but have yet to find the time.

LikeLike

Slightly OT, perhaps, but here is as good a place as anywhere to mention this, I think:

“Hot summer and damp autumn cause UK boom in destructive honey fungus

Huge increase in tree-killing disease is result of climate crisis, experts say”

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2025/nov/01/hot-summer-and-damp-autumn-cause-uk-boom-in-destructive-honey-fungus

“A golden mushroom that grows in clusters and can attack and kill trees has increased by 200% in the UK in a year because of the hot summer and damp autumn.

Recorded sightings of honey fungus are up by almost 200% compared with the same period last year, according to iNaturalist....

...Should people be concerned? In gardens, honey fungus can devastate trees and shrubs, but a bumper year of honey fungus may reflect broader ecological changes.

“Over the last two decades, climate is altering the fruiting patterns of fungi,” said Henk, adding that mushrooms “are a key part of habitats for invertebrates and food for larger animals, too”…..

It’s not climate change – how can it be? One dry summer followed by a damp autumn. Twenty years (at best) of statistics.

By the way, my wife and I spotted a tree in the woods at Loweswater the other day covered in this honey fungus. By the time we returned past it later in the day a team from the National Trust had felled it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We had a dead tree chopped down this year & the mushrooms have exploded from the stump in the last few weeks.

ps – O/T not sure where to post this – Historic Floods: The Climate Story of Edinburgh Castle

It features a nice hockey stick graph credited to Ed Hawkins covering the last 2000 yrs, titled “Global Average Temperature Change” & it includes the “medieval warm period & “little ice age” but notes these were “regional”. So is it Global or not?

The rest of the article is about how Edinburgh castle is “Long-term environmental pressures have been compounded by more immediate and severe climate patterns, bringing increased vulnerability to Edinburgh Castle”.

Reminds me of a comment by (I think) John Ridgeway about Stonehenge not being made of chocolate. But that gets me onto another grip, so will stop there.

LikeLike

dfhunter,

Perhaps this is relevant to your musings:

https://cliscep.com/2022/07/14/climate-change-in-stirling/

LikeLiked by 1 person

“They survived wildfires. But something else is killing Greece’s iconic fir forests

In the Peloponnese, entire mountainsides of Greek fir are turning red and dying due to multiple effects linked to climate breakdown.

In the Peloponnese mountains, the usually hardy trees are turning brown even where fires haven’t reached. Experts are raising the alarm on a complex crisis”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/dec/19/survived-wildfires-drought-killing-greece-fir-forests-aoe

After the usual climate crisis narrative, we get this:

…Bark beetles – particularly those in the Scolytinae subfamily – have emerged as a growing threat to Greece’s already stressed forests over the past two years.

Their name is owed to the fact that the insects bore beneath the outer bark, cutting into the systems trees rely on to transport water and nutrients. Once they establish themselves inside drought-stressed firs, their numbers can rise rapidly. “When a population reaches outbreak levels,” Avtzis says, “it becomes extremely difficult to bring it back under control.”

The phenomenon is not confined to Greece. Bark beetle outbreaks have become a wider European concern, Avtzis says, mirroring patterns seen elsewhere on the continent. “Southern Europe may be more vulnerable,” he says, “but we’re observing similar dynamics in countries like Spain.”…

LikeLiked by 1 person

They are all in the subfamily Scolytinae. 😉

I seriously doubt whether there are any objective changes for the worse here, given the long view.

LikeLike

“Scots pine ‘could be wiped out by climate change’”

Or: no it won’t, you idiot.

Words cannot describe how stupid this story is. The shame is that it was in today’s Telegraph, a paper that is sometimes sensible.

Telegraph link. Maybe paywalled?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That Telegraph story can be accessed here:

https://archive.ph/R1zwg

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jit/Mark – so many quotes I could give from that article, will settle for this –

“Ms Petitt, who has dedicated nearly 40 years to the garden, recalled winters so bitterly cold that chores became impossible. “Some winters we couldn’t even go out and rake leaves because they were all frozen solid. That’s unheard of now,” she said.”

LikeLike