Most Cliscep readers will have heard this news story already. Sometimes otherwise innocuous papers make the news because there is a “worse than we thought” climate change angle, and quite often, there are a range of reactions, from sage nods from the catastrophists to howls of derision from the sceptics.

So it was with “Sustained greening of the Antarctic Peninsula observed from satellites” by Roland et al in Nature Geoscience.

The apparent greening of the Antarctic Peninsula reported by Roland et al has been covered by WUWT and Jo Nova. What attracted me to it? Well, the trigger was just one word in the Nature News report’s title and subhead that I found discombobulating. Which one? Take a guess:

Believe it or not, this lush landscape is Antarctica

Vegetation is spreading at an alarming rate in a place where temperatures are soaring.

Well, it was:

…alarming…

[Although “lush” is a ludicrous adjective, it must be said. Does the author even know the meaning of the word?]

Is vegetation spreading over bare ground ever alarming, wherever it is? Who prefers the ground to be sterile? Does anyone prefer change in the other direction, from green to bare? Of course not (and partly this is our allergy to change of any sort, and our insistence that everything has to stay exactly how it is. Except when it comes to anything other than the natural world? Maybe).

The spread of vegetation is not alarming. The next question is, is it happening? The question after that is, is it because of climate change? And somewhere down the line we might wonder whether tis the direct effect of CO2 fertilisation that is causing the increase, or the temperature rise.

Landsat Flies By

The first land imaging satellites were Landsats. From Landsat 4 in the mid 80s the satellites had an MSS: a multispectral sensor, which can see light beyond the visible light that mere humans experience in the day to day. Here’s what happens. Light from the Big Yellow Thing hits the ground and bounces back up. A bit of that light passes into the satellite’s sensor, and makes a picture. From the 80s till now new Landsats have been launched, but the sensor is the same-ish, and the only difference is the memory and download bandwidth. So it’s easy to see that you just consult the public archive of Landsat pictures, and see how much green there is at place X in each year, and you’ve got an indisputably greening Antarctic.

I said the word “green” there, but that isn’t actually the colour that matters. Think of it like this: snow is green. Yes it is. By which I mean, it reflects green light (and red and blue). So measuring the quantity of green hitting the sensor, by itself, is no good. Instead you use NDVI, which is a measure of greenness, obtained by using the values of two kinds of red light: the visible and invisible (infra-red). The NDVI score for a pixel goes up as the vegetation grows, and so, a higher NDVI equals more plants on the Antarctic Peninsula.

So, the archive is public, the processing is relatively easy, and so it’s a wonder that we had to wait until 2024 for this piece of work. Isn’t it?

I strongly suspect others considered it years ago, but after a moment’s thought, said: “Nah. It’s just a giant mess.”

And if you asked me to do it, I’d say: “It’s possible, but it’s a giant mess.”

And several people may even have peeped at the data and concluded: “It’s an even bigger mess than we thought. It’s just not worth it.”

Why is the Landsat archive such a mess? Well, it’s because of where it is. The Antarctic Peninsula is usually cloudy. It’s also quite snowy, even in the middle of the Austral summer. Snow melts and falls and blows around. The chances of Landsat flying over and getting a good series of shots with its MSS is low. Then there are other issues, including shadows (if no incident light hits a location, it will of course appear black to the sensor). The sun is often low at high latitudes, and shadows are long. Seemingly the co-registration of image pixels is difficult (needed to record the value of two pixels at the same location but at different times). So the data is a giant mess.

Having done the best they could with it, Roland et al duly found an increasing NDVI, and alarmists found it alarming, as they are wont to do. Is the trend real?

Well, maybe. But I don’t think this paper proves as much. But Jit. The later pictures had more green, or higher NDVI, than the early pictures. Greening is the only answer. Maybe. However, I suspect that there may be a contribution from the satellites themselves. The newer Landsats take more pictures. Their sensors are similar to the older satellites, but they have more on-board memory, and can send more data down to the base stations. That being so, you have a higher chance of getting a good cloudless image in later years… and more chance of picking up green areas.

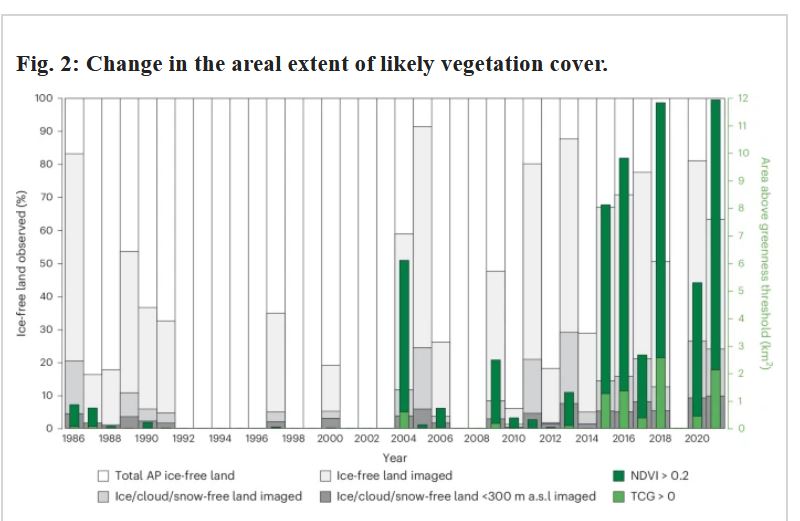

Looking at Roland et al’s Figure 2, there seems to be some evidence of greater image coverage in later years. Without co-registered pixels, we don’t actually know whether some areas begin grey and become green: just that we recorded more green in later years.

There’s something else a tad concerning about Figure 2 as well. Look at the inter-annual variation. Does this bespeak a slow incremental greening to you? The moss banks of the Antarctic Peninsula are often rather old (>4000 years old). They grow very slowly at very low temperatures. The cushion-moss communities that develop on better-drained soils also develop very slowly. But here, we have sudden leaps up in the area classified as plant-covered. And more tellingly, we have sudden drops. Consider the change from 2004 to 2005. The plant cover plummets to a fraction of its former value, but the image coverage is higher. What happened in 2017? Why the drop in apparent vegetation here? Again, there was more coverage than the previous year.

The suspicion is, that image quality is determining the quantity of plants detected, rather than the detected quantity actually representing what is going on on the ground.

[A long technical section on the merits of Roland et al’s methods used to go here, but I’ve excised it: I strongly doubt whether the general reader would have been interested in it.]

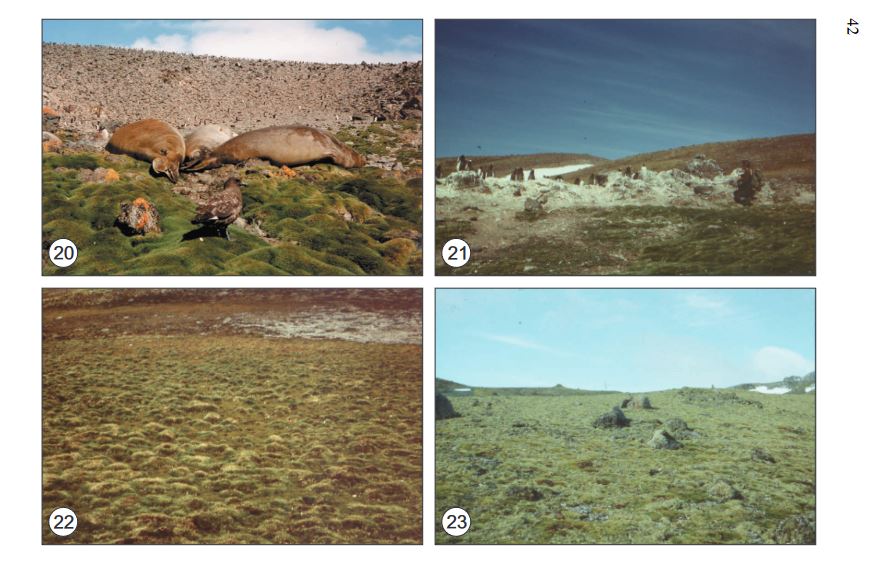

We’ve mentioned that vegetation is developing, if at all, at glacial pace, and that the year-to-year variations don’t conform to that. I would also argue that the initial values are too small. The bryologist Ryszard Ochyra described the moss communities of King George Island (South Shetlands) in 1998 from his work there from the late 1970s onwards. His descriptions of the island do not square with the very low early values of vegetation reported by Roland et al. In 1982, Furmanczyk and Ochyra mapped about 10 hectares of vegetation in a small area by the Polish research station in one bay on one island off the Antarctic Peninsula (Admiralty Bay, King George Island). It is not credible to say that if 0.1 km2 were mapped in this restricted area (albeit the moss-richest) in 1982, that all the vegetation of the entire Antarctic Peninsula covered less than 1 km2 total at that time. Or that Ochyra would write an epic monograph about the mosses of King George, comprising 60 species, and undertaking collections in a hundred locations about the island in 1979-1980… if the entire vegetation of the entire Antarctic Peninsula covered less than 1 km2 at that time.

Ochyra presents some photographs of vegetation on King George in 1980 (see the link at bottom for photo credits). And the total vegetation in the entire Antarctic Peninsula is supposedly below 1km2 at this time? Not credible.

All that said, the vegetation may well have expanded in the past 40 years. This paper does not prove that, but that does not constitute proof that it hasn’t happened. If it has, was it rednecks driving Ford F-150s that did it?

Sceptics have pointed to CO2 fertilisation. Maybe. But this has a strong effect in dry places. And while the centre of Antarctica is dry, its fringes are not. A lot of these moss communities are fed by meltwater and kept damp. So water loss through stomata is maybe not an issue. Of course, when life is marginal, making photosynthesis easier would certainly help. What about temperature? I have not seen the temperature trends of King George and its surrounds. It’s still very cold in the summer. And to invoke temperature, we would have to explain how:

Climate was suitable in a small part of the island of King George in 1980, and a larger part today.

Since temperatures are highly correlated over large distances, does this make any sense? How could places a few metres apart be warm enough for growth and too cold for growth?* It’s worth noting here that the bases of moss banks on King George have been dated as >4000 years old. The vegetation has not just sprung up ex nihilo. [Ochyra notes that shelter from prevailing westerlies has a role in determining the presence of plants. Has climate change the power to alter this?]

ASTERISK: there are microclimate difference across distances of metres. But not on flat ground, or gently sloping ground.

Another possible explanation for vegetation growth on King George relates to the numerous research stations that have been established there. Disturbance from these sites, and from increasingly abundant tourists, may well have caused penguin colonies to relocate. Such places are no longer subject to toxic levels of phosphorus by manuring (but are still nutrient-rich). Highly-trampled areas are trampled no more. Added together, these factors could increase vegetation growth (a point that Roland et al acknowledge).

Areas [on King George Island] that have been abandoned by penguins are rapidly colonized by complex plant formations, facilitated by both the considerable nutrient resources and the cessation of trampling by the birds.

Zwolicki et al, 2015

I’ve gone on too long, haven’t I? Let me just summarise by saying, there is plenty of room for doubt surrounding this story, and as you might guess, doubt is not something that the primitive minds who spoonfeed us our proper opinions are going to place in prominent position.

References

Furmanczyk and Ochyra’s 1982 map of the vegetation of their bit of Admiralty Bay

Ochyra’s monumental work on the mosses of King George Island (1998).

Soliman 2024 (Nature News report on the paper).

Zwolicki et al 2015, Seabird colony effects on soil properties and vegetation zonation patterns on King George Island

A fine analysis, Jit – thank you.

I guessed that “alarming” was the word that triggered you, since it triggered me when I first read it – but not enough to motivate me to write about it. Just as well, really, as you have made a far better job of it than I would have done.

If dramatic changes are occurring, then it’s right that they are brought to our attention, so that we may consider the implications. However, a lot of reporting on anything related to climate change seems to be increasingly unhinged. As you say, if green areas became barren, that would be bad news (potentially alarming, indeed), but the other way around? Really? And what if the greening is nothing like so dramatic as claimed? But that wouldn’t justify a headline, I suppose.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Classical example of a sceptical approach — as was once mainstream in university research seminars but apparently no more. An enjoyable read.

LikeLiked by 4 people

“Believe it or not, this lush landscape is Antarctica

Vegetation is spreading at an alarming rate in a place where temperatures are soaring.“

If “lush” and “alarming” are overstating things, how about “soaring”?

LikeLiked by 2 people