I came across this paper at Retraction Watch, and found its allegations interesting enough to share them here, seeing parallels with climate science.

The paper, by Peer Ederer, was published in Animal Production Science last month.

From the abstract:

Sciences related to animal agriculture are threatened by agenda-driven scientists. (…) Such agenda-driven scientists pursue an a priori mission, whose achievement justifies any means, even if it includes to willfully (sic) manipulate and interpretate data, or to violate good practices of integrity in the sciences.

Ederer reports three case studies, describing them as

Three case studies where science may have or be about to lose its integrity

I’m not going to dwell on the first two, but describe them briefly below. Quotes by Ederer unless made clear otherwise:

The first is about the IARC’s Working Group report on the carcinogenicity of red meat. IARC has form for finding everything in the Universe carcinogenic, including hot drinks and blue lights. They are probably most famous recently for the finding that glyphosate is carcinogenic, leading to giant awards against the manufacturer. Regarding red meat, the author argues that the IARC’s assessment is flawed.

The second is about the Global Burden of Disease’s 2019 report.

When it was published, some observers (concerned scientists) noticed a conspicuous jump of dietary risks and deaths associated with diets high in red meat, compared with the previous GBD 2017. There was a 36-fold increase to a total of 896,000 deaths (GBD 2019, 2020). Deeper analysis of the publication showed that the theoretical minimum-risk exposure level (TMREL) was reduced to 0 g per day, making red meat toxic from the first bite.

The third case study was the extraordinary one, and was titled

Sustainable livestock at United Nations Food Systems Summit 2021

The background is rather complicated. I will try to summarise briefly here, but if you want your statue to have arms and legs as well as a torso, you’ll have to consult Ederer’s paper. This one took place under the aegis of the UN, who wanted to set out a “decade of action” to achieve its sustainable development goals by 2030.

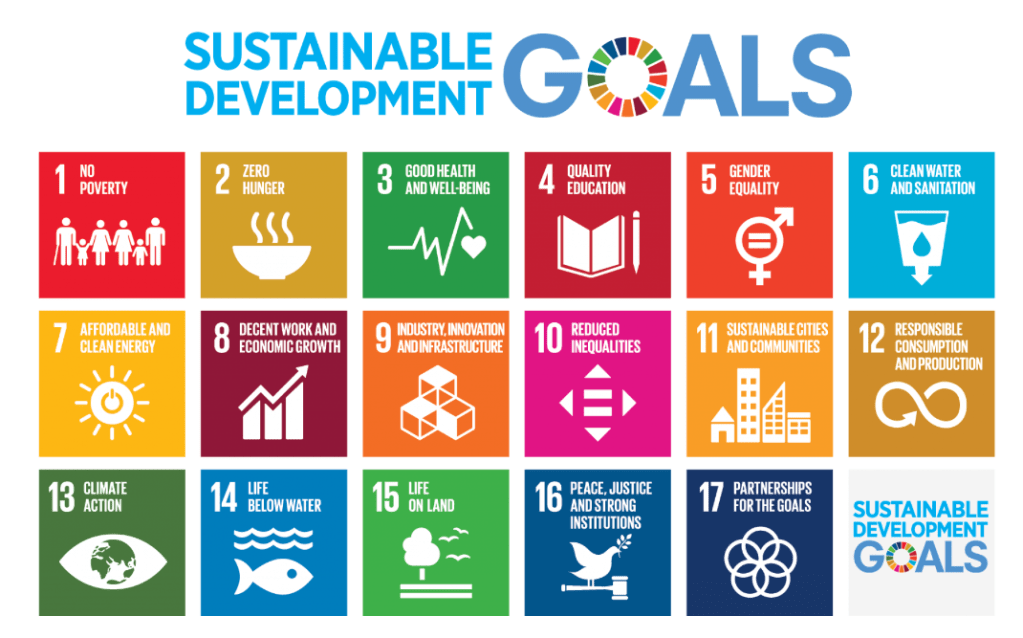

(There are 17 SDGs. How many can you name? Answer at the end.)

As part of this, Antonio Guterres convened a Food Systems Summit via the WEF (November 2020), and five action tracks resulted. The one our author was interested in was Action Track 2, whose theme was a “shift to sustainable consumption patterns.” The Chair of AT2 happened to be the founder and Executive Chair of EAT, “the science-based global platform for food system transformation.”

(Is it just me, or is the phrase “science-based” a red flag these days?)

Without knowing anything about this crew, you may guess at the sort of things they think are good solutions for “food system transformation”. Myself, I don’t think food systems need transformation by a UN body. Give countries the freedom to develop naturally and crop yields will inevitably rise, and unless we force people to do everything by hand, people will eventually farm their way out of poverty; ultimately the land area required for farming will go down. Yes the intensively-farmed land may be sterile, but at least this should spare larger areas for biodiversity. Well, I can dream.

Ederer quotes the 2019 EAT-Lancet report as saying:

The scale of change to the food system is unlikely to be successful if left to the individual or the whim of consumer choice.

Not unlike certain interventions in the climate sphere. Back to his paper:

The public positioning of the choice for AT2 leadership left no doubt, although not explicitly mentioned like this, that the AT2 aims were to significantly reduce the amount of meat consumption, accompanied by a corresponding reduction of livestock, and, by self-declaration as described above, to force through this transformation by authoritarian ‘hard’ measures against the will of the consumer where necessary.

Ederer writes:

By May 2021, the Summit preparations had reached a major impasse. Most of the various stakeholder groups representing farmers, civil society and industry could not find common ground with representatives from AT2 on the role of livestock in a global food system.

To resolve the impasse, Ederer was one of three individuals nominated to compile a 2-page paper summarising the views of 70 organisations on sustainable livestock. He summarises its view on livestock as,

‘Much improvement is necessary, but livestock is part of the solution, not part of the problem’

Naturally, the AT2 folk did not approve, and asked the trio to incorporate points from a further bunch of stakeholders brought in from left field. Ederer quotes some of their responses to the original document:

‘That is nonsense’, ‘On farmer-driven roadmaps: in other areas such as energy, would it be acceptable for oil producers to decide a roadmap?’, ‘It is absurd to proposition a growth in the livestock as a solution’, ‘It is irrelevant that livestock farming has provided food, clothing, power, manure and income and acted as assets, collateral and status. Fossil fuel has done many of the same things’, ‘We are a 38 trillion investor network calling for sustainable agriculture system which importantly includes a shift to plant-rich diets and lower quantities of high-quality meat and dairy consumption’ and similar (these quotes are taken from email conversations that were shared among many members of the solution cluster and therefore are neither private nor confidential).

At this point there was another impasse, because Ederer and his two co-summarisers rejected most of the ideas from the new stakeholders as either not based in science or without known methods to achieve them. It was proposed that the different viewpoints would be presented in three separate 2-page position papers: A, Best Practices and Technologies (substantially similar to the original); B, Grazing for Soil Climate and People, and C, Aligning Production to Consumption. Paper C was the work of EAT-aligned organisations advocating for a shift to a plant-based diet.

Each of the three A, B, C papers was extensively referenced to scientific journal articles, public-policy documents or existing practice descriptions. The Scientific Council of the WFO (World Farmers Organisation) (SC-WFO) checked the quality of the references of each of the three papers (the author of this paper being a co-author of the SC-WFO as well). In the A and B papers, the evaluation found three references each that were not correct, of 45 and 56 respectively. However, among the 53 references of the C-paper, 17 were wrong or irrelevant sources unrelated to the statement, 22 were relevant but said either nothing about or even the opposite of the statement, and 18 sources employed demonstrably weak or manipulative methodologies that could easily be disqualified (multiple mention possible). Only 11 of 53 sources were correctly attributed and supported the statement. That was the quality of the science provided by the C-group, which supposedly was the competence centre of AT2 and EAT on the subject.

One of the papers cited in paper C was Springmann et al 2016, “Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change co-benefits of dietary change.”

In that work, the authors claim to have calculated that if all of humanity switched to a vegan diet, then 8.1 million deaths could be avoided per year on grounds of improved health. The authors claim to have calculated this value based on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) survey 2010. The vegan diet that they composed would avoid the GBD health risks of diets being low in fruit for 4.9 million avoided deaths, and low in vegetables yielding 1.8 million avoided deaths. Avoided deaths because of diets high in red meats falling away due to it being vegan, would contribute only 38,000 cases (according to GBD 2010, each value was extrapolated by some factor to adjust for population growth to then reach a total of 8.1 million avoided deaths). Clearly, the avoided death toll of the preferred diet had almost nothing to do with being ‘vegan’, and all with eating sufficient amounts of vegetables and fruits.

I have not done more than skim Springmann et al 2016, but another contemporary paper led by him advocating a carbon tax on food was discussed at WUWT.

Now, it’s obvious that Ederer has a viewpoint here and is not an entirely disinterested observer. But it’s also obvious that certain scientists have an agenda and are willing to spin results rather shamelessly to portray them as supporting that agenda in an unalloyed way, creating “facts” which vanish like morning dew on close inspection. (A diet of white rice is vegan, and it’s unclear to me how resource-intensive a lot of the foods that make being vegan remotely appealing are.) As to the UN, I’m not sure really what the point of it is, other than to create a vast unaccountable bureaucracy with luxury opinions about every topic you care to name.

Attentive readers will know that I’m a vegetarian. I’m also an old-fashioned liberal, who would not dream of imposing any of my preferences on anyone else. I will even, when I am PM, resist the urge to create a law against public sniffing.

Ederer’s conclusion on identifying agenda-driven scientists:

…agenda-driven scientists may be identified by terms such as ‘scientific consensus’ whose aim it is to choke off debate and proclaim an unchallengeable truth. Knowledge discovering scientists, instead, can be identified by having more questions than answers. Paraphrasing Feynman, the biggest difference between the two is that the airplanes of the agenda-scientists fail to land – always.

Reading the paper, I was struck by the similarities between food science and climate science. When it comes to policy, there is a preferred narrative, which often goes beyond what is defensible based on good-quality evidence. If you are looking for evidence to support your case, look hard enough, and you will find it. Such an approach leaves opposing evidence undiscovered. If a valid summary of climate science is “it’s worse than we thought,” then we know there is something wrong.

Answer to quiz question: here they are (image via DAERA):

Jit,

If you are looking for evidence to support your case, look hard enough, and you will find it. Such an approach leaves opposing evidence undiscovered.

This is very true, of course. Many moons ago I wrote an article that covered the application of evidence theories such as possibility theory (The Confidence of Living in the Matrix). When talking about the confidence one can glean from a body of gathered evidence, I offered the following warning:

So you are not alone when you talk of ‘science-based’ being a red flag, but I would add to that any use of the term ‘evidence-based’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed. What’s so special about climate science?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Science based … evidence based … stake holders …

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been vegetarian for many years, though I will be the first to recognise the health benefits of the consumption of meat and dairy products, including red meat. I stopped eating meat because I could not support the gross animal cruelties inherent in the mass production of meat. Those cruelties still exist and they are becoming worse, as farming methods switch from natural grazing and free range practices to intensive factory farming, even of cattle. You would think that opposing factory farming and encouraging kinder methods of animal husbandry and meat production, throughout the production chain, would be the main focus of greens, but it isn’t. They want you to stop eating meat per se, because it isn’t ‘climate friendly’ and they bolster their case by claiming also that eating meat and dairy is not healthy, using pseudoscience to do so.

The mass consumption of cheap, factory farmed animal protein necessarily involves huge animal suffering. It is entirely reasonable to ask people to spend more on meat products, but consume less, by choosing higher quality free range meat produced on farms where animal welfare is a priority. It is NOT reasonable to say to people: ‘Stop eating meat and dairy or the climate gets it.’

This is the authoritarian, pseudoscientific position of the UK Green Party:

Animal welfare is mentioned almost as an afterthought amongst a long list of priorities:

https://policy.greenparty.org.uk/policy/food-and-agriculture/#FA202

It’s mostly UN Agenda 2030 ‘sustainable’ claptrap, when the main focus should be animal welfare, not the protection of the planet from an imaginary ‘climate crisis’ by socially engineering the human diet.

LikeLiked by 3 people